The human body is equipped with remarkable defense mechanisms to protect against the constant threat of microbial invasion. At the forefront of these defenses is the epithelial barrier—a physical and biochemical shield that prevents pathogens from entering your body. This barrier is not only the first line of defense but also a critical determinant of whether an infection can take hold. As long as the epithelial barrier remains intact, it acts as an impenetrable wall, thwarting pathogen infiltration and the onset of infection.

However, when this barrier is breached, the body’s immune system is activated. From the rapid deployment of innate immune cells to the precise, targeted responses of adaptive immunity, the process of combating infection is both complex and dynamic. This article explores the pivotal role of epithelial integrity in preventing infections, the immediate actions of innate immune cells, and the adaptive immune system’s specialized responses in containing and eliminating microbial threats. By understanding these processes, we can gain insight into how the body maintains its delicate balance between health and disease.

The Role of Epithelial Integrity

The first critical step in the infectious process is the adherence of the bacteria to the epithelial surface. This initial interaction is a prerequisite for the establishment of infection. However, as long as the skin barrier remains intact, bacterial adherence and subsequent infection cannot occur.

The Role of Tissue Macrophages and Dendritic Cells

Beneath the epithelial barrier lie tissue macrophages and dendritic cells, which serve as the immune system’s first line of defense. When the skin barrier is breached—whether by injury, trauma, or other means—bacteria are introduced into the tissue environment below the epidermis (skin).

If the bacterial inoculum (number of bacteria introduced) is small, pre-formed proteins in the tissue resident phagocytes, which include macrophages and dendritic cells, can rapidly eliminate the invaders before they establish an infection. These proteins are stored in granules within the phagocyte and are released right after the phagocyte engulfs the bacteria, generating a toxic environment that destroys the pathogen. Once engulfed by the phagocytes, the bacteria is broken down and digested in the acidic environment of the phagolysosome. This efficient clearance often prevents further immune activation.

High Inoculum or Virulent Bacteria: A Challenge for Immunity

When the invading bacteria are particularly virulent or replicate rapidly—or if the bacterial inoculum is large—there is a significant risk of high levels of bacterial replication and tissue destruction. Under such circumstances, the immune system must mount a stronger response through the:

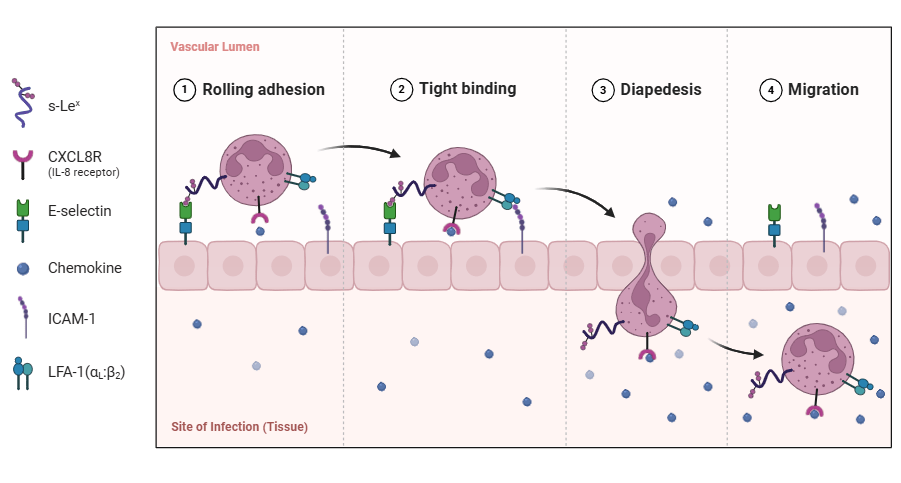

- Recruitment of Additional Immune Cells: Tissue macrophages and dendritic cells recruit additional immune cells from the bloodstream by releasing signaling molecules. Monocytes from peripheral blood migrate to the infection site through a process called extravasation, during which they roll along the blood vessel walls. Once the monocyte reaches the site of infection, it migrates from the blood vessel into the tissue through a process called diapedesis, where they differentiate into macrophages to help control and eliminate the infection.

- Induction of Blood Clotting: To contain the spread of infection, the body may initiate localized blood clotting. This prevents bacteria from disseminating into surrounding tissues, creating a physical barrier to their movement.

Extravasation is the process by which white blood cells (leukocytes) migrate from the bloodstream to the site of infection, crossing the blood vessel walls to reach the affected tissue.

Activation of Adaptive Immunity

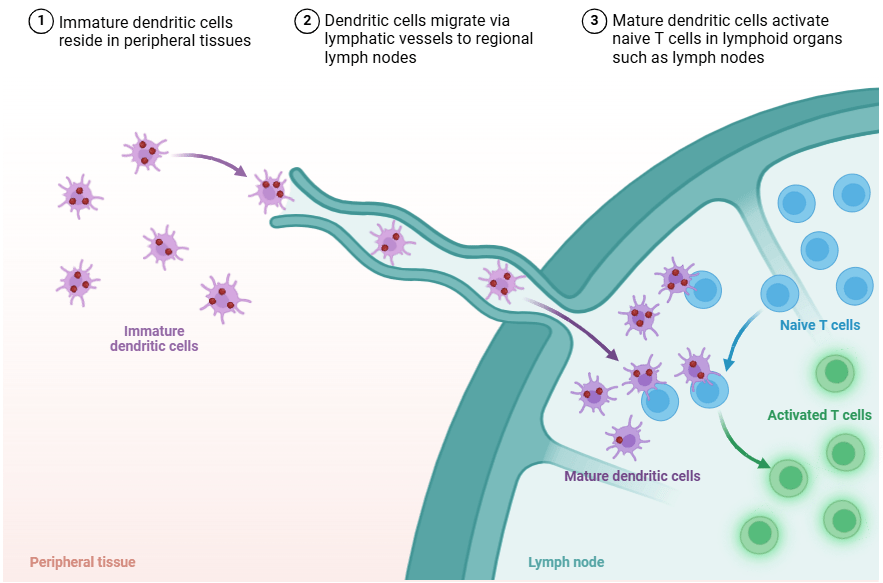

If the infection surpasses the control of innate immune responses, the adaptive immune system is then activated. This process involves:

- Antigen Presentation and Lymph Node Activation: Bacterial antigens are transported to lymph nodes, where they stimulate specific adaptive immune responses. B cells proliferate and produce antibodies targeting the bacterial antigen. Simultaneously, T cells, particularly helper T cells, are activated upon recognition of the specific antigen.

- Recruitment of T Cells and Antibody Circulation: Activated T cells are recruited to the infection site to assist in controlling the bacteria. Activated T cells enhance the bactericidal activities of phagocytic cells through the release of cytokines (immune signaling molecules), like IFNγ. Antibodies produced by B cells in the lymph nodes enter circulation and migrate to the site of infection. These antibodies can efficiently cross the more permeable blood vessels in inflamed tissues.

- Bacterial Clearance: Antibodies bind to bacteria, facilitating their elimination through two primary mechanisms:

- Phagocytosis: Antibodies act as opsonins (extracellular proteins), which mark bacteria for engulfment and destruction by phagocytic cells.

- Complement Activation: Antibodies can activate the complement cascade, which directly lyses bacterial cells or enhances phagocytosis.

Conclusion

The infectious process is a dynamic interplay between the invading pathogen and the host’s immune defenses. While an intact epithelial barrier prevents bacterial adherence and infection, breaches in this barrier initiate a cascade of innate and adaptive immune responses. The immune system’s ability to efficiently recruit and activate the appropriate defenses determines whether the infection is contained or progresses to more severe tissue damage and systemic involvement.

In our upcoming Immunology Blog, we’ll explore in greater detail how the innate immune system defends against infections and protects the body!