“Science is a way of knowing – an approach to understanding the natural world” (Campbell Biology). Our insatiable curiosity to learn more about ourselves, other organisms, and our planet has truly become the basis of modern science. The human race’s desire to learn more about the natural world has created the study of science. The word “science” itself derives from a Latin verb meaning “to know”. Embarking on the journey to further understand the processes of the world around us is one quality that has come to define us as humans.

Inquiry, the search for explanations of the natural phenomena of our world, is integral to science. Though some might think that there is a set process by which scientific discoveries are made, there really isn’t a rigid formula for conducting a scientific inquiry. Each scientist or group of scientists has their own unique method that they develop and use to find the answers to their inquiry. In scientific quests, all researchers experience their own obstacles, challenges, adventure, and surprisingly luck, in addition to the careful planning, analysis, creativity, preparation, and perseverance that comes along with such a difficult task of discovering the truth of the unknown. These aspects of science are what truly make this field so unpredictable and unorganized. However, there is a basic structural formula that scientists follow in order to better describe and explain nature in their scientific explorations.

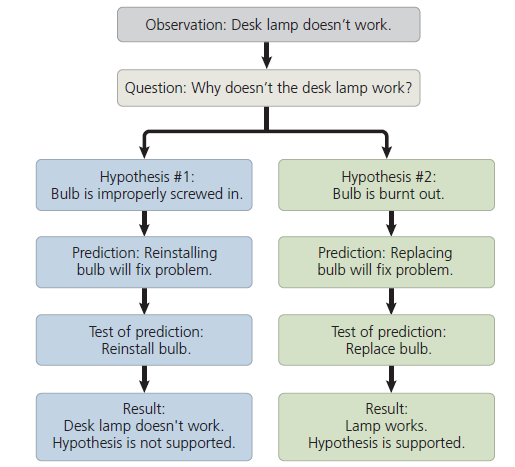

Scientists utilize a process of inquiry that includes the following components: observations, forming potential explanations for a phenomenon (hypothesis), and testing their ideas. This process is a repetitive one, but for good reason. The majority of the time, a researcher’s initial hypothesis will always be inaccurate, so the repetitive nature of this scientific cycle allows scientists to develop their initial hypothesis and conduct experiments to determine its validity. If new observations prove to invalidate the current hypothesis, researchers have the opportunity to go back and rework it (such observations push researchers to go back to the drawing board and revise their hypothesis), thereby creating a new one and continuing the cycle once again. Through this ‘scientific process’, scientists are able to get closer and closer to their most accurate conclusion of the “laws that govern nature”.

The innate curiosity of humans motivates us to question the basis and inner workings of the phenomena we observe around us. For instance, what causes fish, such as salmon, to swim back to their birthplace to lay their eggs? By qualifying their inquiries, biologists, specifically, are able to rely on previous research by other scientists. Through reading and learning from past studies, current scientists are able to build upon existing scientific knowledge, and instead focus their research on novel observations and construct their hypothesis to be based on previous findings. Currently, conducting research through the aforementioned process is much easier than in the past due to the rise of electronic databases and journals.

While conducting research, biologists make a series of detailed observations. When making such observations, they use various tools, such as microscopes, spectrophotometry, and high-speed cameras. These tools not only allow scientists to further their possibilities in terms of observations, but they also allow them to collect more accurate data. Observations, as many of you, may know, reveal valuable information about our world. Whether it be noticing that some trees change color during autumn while others don’t, or that water reflects the color of whether it faces or is in, observations allow us to learn more and further understand our world. For example, a series of careful and intricate observations have shaped the scientific community’s understanding of cell structure and foundation, while other observations are currently expanding our knowledge of genetic mutations of various diseases.

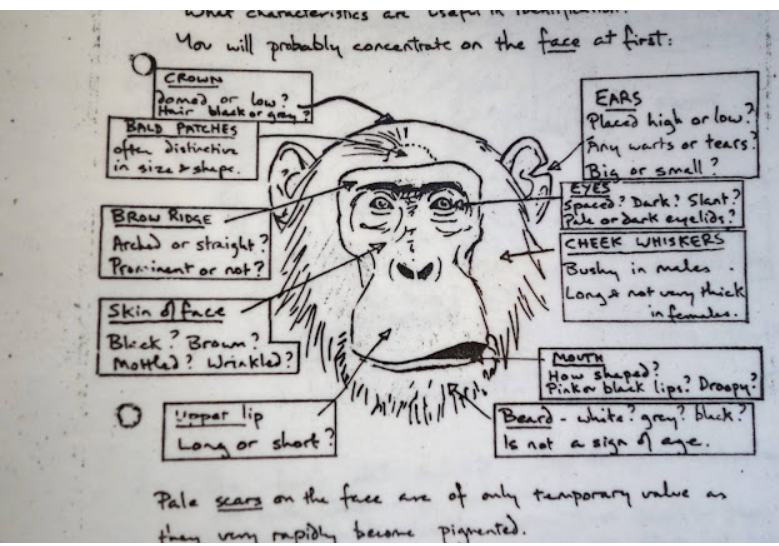

Recorded observations are defined as data. In other words, data is the information that scientific discovery is based on. Only if there is data supporting a hypothesis will that hypothesis be considered to be true and added to our cumulative scientific knowledge. Something can only be considered a discovery if, and only if, there is clear scientific proof supporting it, also known as data. Many people usually associate data with quantitative numbers. However, data can also be qualitative, usually in the form of descriptions of phenomena instead of math and numbers. Jane Goodall, for instance, spent decades recording her observations of chimpanzee behavior during her research expeditions. The only time number and math-based data were included in her research was when she recorded the frequency, duration, and probability of certain chimp behaviors. However, the lack of math-based observations does not invalidate the fact that her observations are significant data that has revolutionized human understanding of ape behavior and interactions. In addition to the raw data collection through observations, scientists also analyze their data through statistics, a form of mathematics, that determines whether or not the results from their observations truly have a meaning behind them or are simply random coincidences.

Through the collection and analysis of observations, scientists can draw accurate conclusions based on inductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning, a form of scientific logic, allows researchers to extract a series of generalizations and broad-spectrum conclusions from a set of observations. A common example of such a generalization is “all organisms are composed of cells.” Detailed observations and data analysis, paired with general conclusions that are a product of induction, are fundamental to the scientific community’s current understanding and future discoveries of nature.

After gathering initial observations and analyzing them, scientists form temporary explanations, or so-called answers, to their original questions that they will test with further experiments. These tentative explanations, in the scientific world, are known as hypotheses. A hypothesis is a testable explanation derived from observations. The word ‘testable’ in the previous statement is the key, as there is no use in creating a hypothesis that one can not test. Scientists usually can not test an idea that they have due to a lack of knowledge in that field or underdeveloped technology. Therefore, a hypothesis must be able to be tested by an experiment, which is, simply put, a scientific test executed under controlled conditions.

What comes as a surprise for most people is that we all make observations and formulate hypotheses when trying to solve our everyday problems. For example, you notice that when you turn off the faucet after washing your hands in the kitchen, the kitchen sink does not drain the water. This is an observation – something that you observe about a certain situation. You then ask yourself, “why isn’t the sink working”? As a result of pondering this question, you come up with two possible explanations. The first is that there may be food from the dishes that are stuck in the sink pipes and is preventing the water from draining out of the sink. The second explanation is that the pop-assembly of the sink that controls the drainage has been accidentally locked. Each of these hypotheses leads to you making predictions that you will test to solve your sink clogging problem. The process of solving problems and making discoveries through a trial-and-error process is a hypothesis-driven approach.

The usage of hypotheses in science is also complemented by the integration of deduction, a type of problem-solving and observation-based logic. When comparing induction to deduction, you may notice that induction involves using a series of specific observations to arrive at a general conclusion. However, deductive reasoning heads in the opposite direction, from general to specific. The concept of deduction in science may seem counterintuitive to some, and you may ask the following question – when you are trying to make a discovery using the scientific process, wouldn’t you only know the generalities of that topic, and then through experimentation, gain more specific knowledge? How could you possibly move from specific to general? However, from general premises, scientists are able to predict the type of results that they should get if those premises are proved to be true through experimentation. During experimentation, deductive testing takes the form of “if … then” logic. Referring back to the clogged sink example, if the food stuck in the pipe hypothesis is correct, then the sink will work again after you remove the food from the pipes.

Using the sink example once again, there are two main ideas to understand when using hypotheses in science. The first key point is that multiple hypotheses can be created to explain the same set of observations. For instance, another hypothesis that explains why the sink is not draining water is that the pop-assembly control is closed and locked, thereby preventing water from draining from the sink. Designing an experiment to test your hypothesis would be a great way to prove its validity; however, it is important to note that many hypotheses can not be tested by experimentation. The second idea is that a hypothesis can NEVER be proven to be true. For example, the food in the pipe hypothesis is by far the best explanation for the sink not draining, but the experiments conducted support this hypothesis – NOT by proving that it is true, but instead by FAILING to prove that it is INCORRECT. This just goes to show that hypotheses can never be proven to be completely true. However, testing our hypothesis in various ways can work to increase our confidence in its validity and accuracy. What truly solidifies a hypothesis as true in scientific history is when several rounds of experimentation lead to a scientific consensus that is a shared conclusion by a variety of qualified scientists who believe that the hypothesis truly explains the “why” behind the data and is validated by rigorous testing.

As covered previously, scientific inquiry is truly unique and allows scientists to better understand nature. However, there are glaring limitations to this technique. A scientific hypothesis must be testable, which means that data from an experiment must either conclude that the hypothesis is either true or false. For example, the hypothesis that food clogging the sink was the only reason the sink would not drain would not be supported if all the food was removed and the sink still did not drain. Therefore, not all hypotheses are truly scientifically testable. If you hypothesize that there are ghosts in your bathroom, what experiments could you perform to prove this statement? You truly are unable to test this idea. Hypotheses that can be proven through scientific inquiry must deal with the natural world, something that truly exists, and not something that is supernatural or magical. Supernatural phenomena and other magical events are outside of the bounds of science, and therefore, scientific inquiry is unable to test or prove these ideas.

In our next basic biology blog, we will continue to explore the processes of experimentation through a scientist’s lens. Not only will we cover the flexibility of the scientific process, but we will also discuss the diversity in the scientific thought process.

One thought on “The Scientific Method”