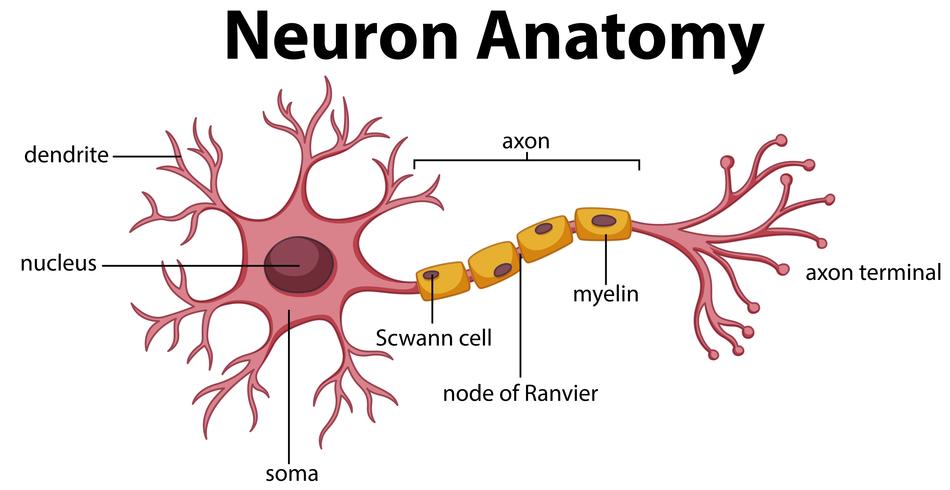

Although there are many different kinds of neurons in the nervous system, the same basic electrical principles underlie their function. Before we can get into the complexities of neuronal signaling, let us take a look at the electrical principles that are in play when the cell is at rest. When you look at a typical neuron, you can see that it has a variety of parts that allow it to function. All neurons have a soma, also known as the cell body, which houses the cell’s nucleus and other cellular machinery. Extending out of the cell body are fine processes called axons and dendrites. The outer surfaces of all the neuron’s parts are composed of a bilayer of lipid molecules that separate the inside of the cell from the outside. This lipid bilayer is referred to as the cellular membrane. Before we can start looking at the whole neuron and its various parts, we are going to use a small patch of neuronal membrane located in the soma to understand the concept of resting potential.

There is so much happening in one tiny patch of the neuronal membrane. Even when the cell is “at rest”, it is not electrically neutral. An important term to remember when learning about neurology is voltage. Voltage refers to the difference in electrical potential energy across the membrane. The term electrical potential describes the strength and direction of the forces that motivate electrical charge flow based on electrostatic forces between charged objects. Electrostatic forces, which play a crucial role in the potential of a neuron, describe the attraction and repulsion between ions, which are negatively or positively charged particles. The rules of electrostatic forces are that opposite charges (-, +) attract while the same charges (+, + & -, -) repel. If you measure the voltage between the inside and outside of a neuron, you will come across a small but important voltage known as the membrane potential. Membrane potential describes the voltage across the membrane at any point in time. The membrane potential of a neuron can vary widely, from -90 millivolts (mV) to +60 mV.

Most people might be familiar with the idea of potential energy or stored energy. An electrical potential is very similar to that idea. In neurology, an electrical potential is characterized as the potential an ion has to move towards a more positively or negatively charged ion. For instance, a battery generates an electrical potential or voltage between its positive and negative ends. When we hook up a wire across the two terminal ends, the electrical potential causes electrons to flow through the wire from the negative terminal to the positive one. We can harness the flow of electrons to do work, such as lighting up a light bulb. If we measure the potential difference between the inside and the outside of a neuron at rest, we will receive a voltage reading of approximately -70 mV (millivolts).

It is crucial to understand that the separation of charge creates a potential. For example, let’s take a neuron which is positively charged on the inside and negatively charged on the outside. We can call the inside of the neuron “point A” and the outside of the neuron “point B”. The potential created by points A and B would cause a positively charged ion to move towards the negatively charged area, which is “point B”. The potential between the two points would also be characterized by a negatively charged ion moving towards point A, which is a positively charged area. When discussing ions, it is always important to remember that opposite charges attract and the same charges repel.

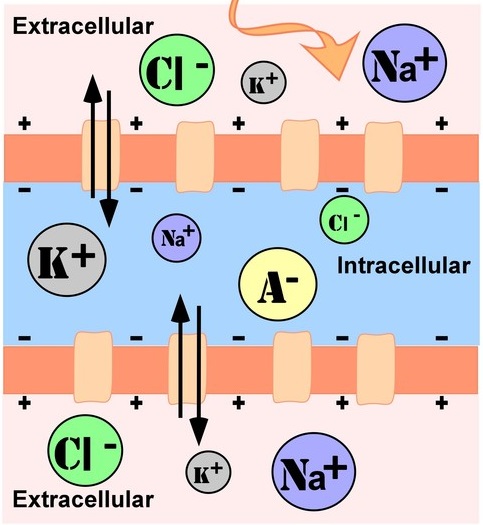

In neuroscience, relevant points are designated to be the inside and outside of the cell, which is separated by a membrane that is impermeable to ions. Ions cannot flow across this cell membrane without the help of channels or pumps, which we will learn about in the upcoming blogs. So, ions can move through membrane channels and form a charge difference between two points which results in a potential and voltage across the membrane. The impermeability of the cell membrane allows the voltage to be maintained. The maintenance of the voltage is similar to the buildup of charge across a capacitor in an electrical circuit.

Voltage is a relative quantity, so we can only really talk about the voltage when it refers to two points. When we say that the voltage, at a particular point in a circuit, is a certain number of millivolts, we also need to define what point we are considering to be zero. Neurophysiologists consider the outside of the cell to be this 0 mV, which in electrical terms is called the “ground”. Voltages inside of the cell are measured with respect to this extracellular ground. In other words, neuroscientists use the outside of the cell as the reference point to measure the voltage across the membrane. For example, let’s take the intracellular and extracellular space of a neuron. The extracellular space, which is the outside of the neuron, will be the reference point that we would use to determine the voltage measurement. Let’s say that the inside of the neuron is 50 mV more negative than the outside of the neuron. This means that the voltage measurement is -50 mV because it is the difference in voltage between the inside and outside of the neuron.

To give you some perspective on neuronal cellular voltage, take a look at a double-A battery. A double-A battery has an electrical potential of 1.5 Volts. Comparatively, the resting potential in the cell, which is -70 mV, is twenty times smaller than the magnitude of a double-A battery. Overall, the neuron has a small, but a significant voltage across the cell membrane. The resting potential of a neuron is not structured like a battery because batteries, like the double-A, generate voltages through chemical reactions, specifically electrochemical reactions that release electrons on one side of the battery and use up the electrons on the other side. The key to understanding how electrons generate an electrical potential lies on either side of the cellular membrane.

Both the inside and outside of the cell are composed mostly of water (H20) in addition to other substances such as proteins like collagen, ions like sodium (Na+) and potassium (K+), and sugars like glucose. There is a variety of charged ions and molecules floating in and around the cell, including magnesium (Mg 2+), bicarbonate, phosphate, sulfate, and other proteins. For now, we will be focusing on the most important charged ions to neuronal function, which are sodium(Na+), potassium(K+), calcium(Ca++), and chloride(Cl-). These ions are present in high concentrations in the body and are important in generating a resting potential in the neuron.

Overall, voltage and electrical potentials play a huge role in the processes and basic functions of a neuron. In the upcoming neuroscience blogs, we will be covering the concept regarding diffusion and electrostatics, which is the method by which neurons function.

One thought on “Resting Potential & Voltage”