When we think of tissues in the body, most people picture muscles that move us or skin that protects us; but one of the most versatile and essential types of tissue is connective tissue, which is the biological “glue” that holds everything together within our body. Connective tissue doesn’t just bind and support; it cushions, protects, stores energy, transports nutrients, and even helps fight infections. Without it, the body would lack both its framework and the system to maintain it.

In this blog post, we’ll explore the general characteristics, cell types, fibers, and major categories of connective tissue, all from the flexibility of areolar tissue to the rigidity of bone.

General Characteristics

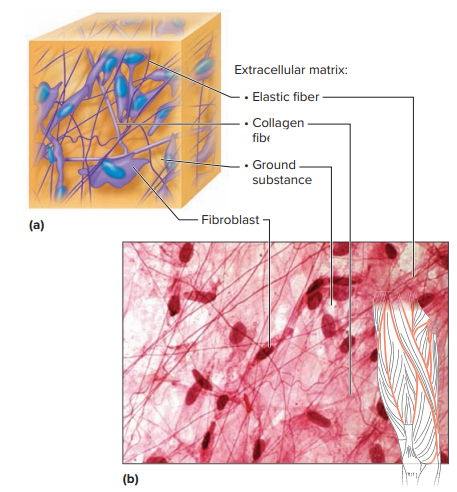

Unlike epithelial tissue, where cells are tightly packed, connective tissue cells are spread apart, separated by a rich extracellular matrix. This matrix is a mix of:

- Protein fibers for structure and strength

- Ground substance, which is a gel-like or fluid medium of nonfibrous proteins, water, and other molecules

The consistency of the matrix varies widely and depends on the location of the matrix:

- Fluid consistency of the matrix in the blood

- Semisolid matrix consistency in the cartilage

- Solid consistency of the matrix in the bone

This diversity allows connective tissue to play multiple roles in the body, which includes:

- Binding structures together

- Providing support and protection

- Filling spaces between organs

- Storing fat

- Producing blood cells

- Defending against infection

- Repairing tissue damage

Most connective tissues have a rich blood supply (vascularity), which supports rapid healing. However, the extent of vascularity can vary; for example, dense connective tissue heals slowly because it has fewer blood vessels.

Major Cell Types in Connective Tissue

Fixed Cells (long-term residents)

- Fibroblasts: Large, star-shaped cells that produce fibers by secreting proteins into the matrix. These are the most common connective tissue cells.

- Mast Cells: Found near blood vessels; release heparin (prevents clotting) and histamine (triggers inflammation and allergic responses).

Wandering Cells (temporary residents)

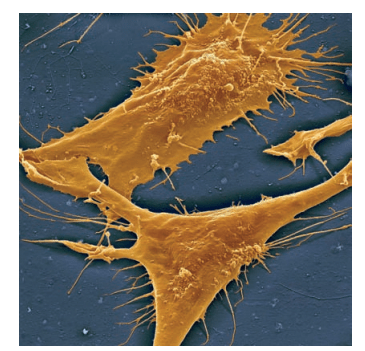

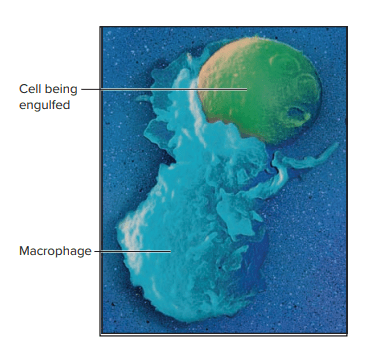

- Macrophages: Derived from white blood cells, they roam tissues to engulf and destroy bacteria, debris, and foreign particles (phagocytosis).

Connective Tissue Fibers

Connective tissue fibers are produced mainly by fibroblasts; these fibers give each connective tissue its unique properties.

- Collagen Fibers (White Fibers)

- Thick, strong protein strands with high tensile strength

- Found in tendons (muscle-to-bone) and ligaments (bone-to-bone)

- Provide structural integrity and resist pulling forces

- Elastic Fibers (Yellow Fibers)

- Made of elastin; can stretch and recoil

- Found in tissues that require flexibility (e.g., vocal cords)

- Reticular Fibers

- Thin, branching collagen fibers forming delicate networks

- Provide soft structural support in organs like the spleen and liver

Categories of Connective Tissue

Connective tissue is grouped into connective tissue proper and specialized connective tissue.

1. Connective Tissue Proper

Loose Connective Tissue (takes up more space, but fewer fibers)

- Areolar Tissue: Binds skin to organs, fills spaces between muscles, nourishes nearby epithelial tissues.

- Adipose Tissue (Fat): Stores energy, cushions organs, and insulates the body. Comes in:

- White fat: Long-term energy storage

- Brown fat: Generates heat (abundant in infants, limited in adults)

- Reticular Tissue: Creates a soft framework for organs like the spleen and liver.

Dense Connective Tissue (closely packed collagen fibers)

- Found in tendons, ligaments, deep skin layers, and protective coverings of organs.

- Strong but has poor blood supply, so healing is slow.

2. Specialized Connective Tissue

Cartilage

- Rigid yet flexible framework with chondrocytes (cartilage cells) in lacunae, surrounded by matrix and covered by the perichondrium.

- Types:

- Hyaline Cartilage: Smooth, glassy; found in joints, nose, and respiratory passages.

- Elastic Cartilage: Flexible; found in the ear and larynx.

- Fibrocartilage: Very tough; acts as a shock absorber (e.g., spinal discs, knee menisci).

Bone (Osseous Tissue)

- Most rigid connective tissue, hardened by calcium salts and reinforced with collagen.

- Supports and protects the body, stores minerals, and produces blood cells.

- Organized into osteons in compact bone for nutrient delivery and waste removal.

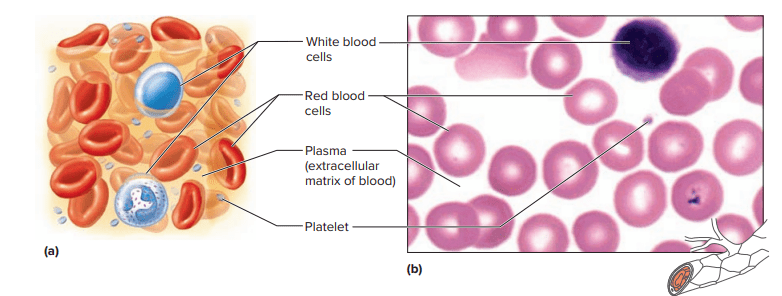

Blood

- A fluid connective tissue that transports gases, nutrients, hormones, and wastes.

- Composed of:

- Red blood cells

- White blood cells

- Platelets

- Plasma (the liquid matrix)

Why Connective Tissue Matters

Connective tissue is more than just structural filler; rather, it’s a living network essential for movement, healing, immunity, and maintaining homeostasis. Whether it’s collagen in your tendons letting you lift weights, adipose tissue keeping you warm in winter, or bone marrow producing blood cells that fight infection, connective tissue keeps every system running smoothly.

Key Takeaways

Overall, connective tissue is remarkably diverse, ranging from the soft, cushioning consistency of fat to the rigid structure of bone. This diversity is largely dictated by the composition of the extracellular matrix, specifically, the types and arrangement of fibers and the consistency of the ground substance, which together determine each tissue’s mechanical and functional properties. Within these tissues, different cell types carry out specialized roles: fibroblasts are the builders that produce fibers and ground substance; macrophages act as the immune defenders, engulfing pathogens and debris; and mast cells play a regulatory role in inflammation by releasing histamines and other signaling molecules. Each subtype of connective tissue is finely tuned to its location and function in the body, whether it’s providing flexibility in tendons, cushioning in adipose tissue, tensile strength in ligaments, or nutrient transport in blood. This specialization highlights how structure and cellular composition enable connective tissues to perform a wide array of essential biological roles.

Source Used: Welsh, C., & Prentice-Craver, C. (2023). Tissues (Chap. 5, pp. 112–119). In Hole’s essentials of human anatomy & physiology (16th ed.). McGraw Hill.