Why Tissues Matter

If you’ve ever looked through a microscope, you know that cells are tiny, but together, they form the very fabric of life. In the human body, these microscopic building blocks don’t just float around on their own; they team up to form tissues, which are organized groups of similar cells working toward a common goal. Broadly, the body relies on four major tissue types:

- Epithelial tissue acts as your body’s shield and gatekeeper, covering surfaces, lining organs, and managing what gets in and out through absorption, secretion, and protection.

- Connective tissue is the structural support crew, holding things together and cushioning your organs.

- Muscle tissue powers every movement you make, from sprinting down the street to the steady beat of your heart.

- Nervous tissue is your communication network, sending electrical messages that coordinate everything you do.

This blog today will explore epithelial tissue, while also setting the stage for how tissues are studied and recognized.

Reading Slides vs. Reading Reality: Tissues Are 3D

Most of what you see in histology (study of the structure of tissues) are micrographs, which are photos of thin tissue sections. Thin sections make light microscopy possible, allowing us to individually see cells; however, they compress a three-dimensional world into a two-dimensional image. That means two things:

- A single micrograph can show more than one tissue type, as well as the boundary between different tissues (for example, epithelium sitting on connective tissue).

- Orientation of the tissue section matters. Cutting a tube at an angle (oblique section) looks different from cutting along its length (longitudinal section). Based on how you slice your tissue, you can see different structures and components of that tissue.

Takeaway: When you study a slide, always ask: What’s the 3D structure I’m looking at, and which plane was it cut in?

Epithelial Tissue: General Blueprint

Where You’ll Find It

Epithelium covers your body’s surfaces, lines body cavities and hollow organs, and builds glands. One surface is always free (apical); this means that the surface is not blocked off by anything. An apical surface is usually exposed to the outside world or to an internal space within the body (a lumen). In contrast, the basal side of a surface anchors that surface to underlying connective tissue via the basement membrane, which is a thin, nonliving layer that acts like a molecular Velcro and filtration barrier.

Key Properties of Epithelia

- Avascular but nourished. Epithelia lack blood vessels, so nutrients diffuse up from the richly vascular connective tissue located underneath.

- High turnover rate. Epithelial cells divide readily, so injuries (like abrasions) heal quickly. This is why skin and intestinal linings constantly renew, with damaged and old cells being replaced by new and healthy ones.

- Tight packing. Intercellular junctions keep epithelial cells close together, allowing epithelia to serve as effective barriers against mechanical stress, water loss, and pathogen infiltration.

- Versatility. Depending on location, epithelia can specialize in different functions, including protection, secretion, absorption, and excretion.

How We Classify Epithelia

The classification or name of epithelial tissue is defined by 2 factors: cell shape and number of layers.

- Shape:

- Squamous – thin and flat (like floor tiles)

- Cuboidal – roughly equal height and width (cubes)

- Columnar – taller than wide (columns)

- Layers:

- Simple – single cell layer (efficient exchange/transport of nutrients)

- Stratified – multiple layers (used for durability and protection)

- Pseudostratified – looks like it has multiple cell layers (stratified) when viewed under the microscope, but in reality, it is a single layer of cells. The illusion of layering happens because:

- The nuclei of the cells are positioned at different heights within the cells, making the tissue look uneven.

- The cells themselves vary in shape and size, with some being tall and others are shorter, but every cell’s base is anchored to the basement membrane.

- Not all cells reach the apical surface (the free surface facing a lumen or the outside), but they still maintain contact with the basement membrane at their base.

Apical modifications to the epithelial surface reflect the function of that specific epithelia:

- Cilia: larger, hair-like structures that contain microtubules and can be motile, facilitating movement of fluid, mucus, or other substances across the cell surface

- Microvilli: smaller, finger-like projections that are non-motile and are primarily involved in increasing surface area for absorption.

- Goblet cells: unicellular glands that secrete protective mucus

The Major Epithelial Tissue Types (What They Look Like, Do, and Where They Show Up)

1) Simple Squamous Epithelium

Structure: One layer of very thin, flattened cells with broad, thin nuclei.

Function: Rapid diffusion and filtration; serves as a minimal barrier for gas/solute movement.

Locations: Alveoli (gas exchange in lungs), capillary walls, inner lining of blood and lymph vessels, and serous membranes that line body cavities and cover organs.

Clinical note: Its delicate nature makes it easy to damage, which is a trade-off for speed of diffusion.

2) Simple Cuboidal Epithelium

Structure: One layer of cube-shaped cells with central spherical nuclei.

Function: Secretion and absorption of substances (like enzymes, hormones, glandular products, ions, or water); Also forms and modifies tubular fluid; in structures like kidney tubules, this epithelium lines the walls of the tubules where blood is filtered into a fluid called tubular fluid (the precursor to urine). As the fluid moves along the tubules, these cells adjust its composition by selectively reabsorbing needed substances back into the blood or secreting additional waste products into the fluid.

Locations: Kidney tubules, ducts of certain glands, and ovarian surface.

Orientation tip: In tubules/ducts, the apical side faces the lumen (the hollow channel).

3) Simple Columnar Epithelium

Structure: One layer of tall cells with elongated nuclei that are aligned near the basement membrane. Can be ciliated or nonciliated.

Functions:

- Protection by forming a thicker epithelial sheet

- Secretion of digestive fluids

- Absorption of nutrients, which is enhanced by microvilli

- Mucus production by goblet cells

Locations:

- Nonciliated tissue: Uterus, stomach, small and large intestines

- Ciliated tissue: Female reproductive tract, where the cilia function to move the egg through the uterine tube

Recognition tip: Look for a “brush border” of microvilli and interspersed goblet cells.

4) Pseudostratified Columnar Epithelium

Structure: Appears multilayered because nuclei sit at different heights, but every cell reaches the basement membrane. Frequently ciliated and goblet cells (which produce muscus) are common.

Function: Trap and clear particles; the mucus that is produced by goblet cells captures dust and microbes, and the cilia sweep the mucus out.

Location: Respiratory passages.

Lab hint: A ciliated surface with scattered goblet cells and nuclei at many levels usually signals pseudostratified columnar epithelium.

5) Stratified Squamous Epithelium

Structure: Many layers; basal cells divide and push maturing cells toward the surface, where they flatten.

Two forms:

- Keratinized (dry surface): Epidermis of skin, where cells accumulate keratin, harden, and die, forming a tough, water-resistant barrier.

- Nonkeratinized (moist surface): Oral cavity, esophagus, vagina, anal canal, where surface cells remain alive and moist.

Function: High-abrasion protection and barrier against fluid loss and entry of chemicals/microbes.

6) Stratified Cuboidal Epithelium

Structure: Two or three layers of cuboidal cells lining a lumen.

Function: Protection with some conduit support as many stratified cuboidal epithelia line the ducts (conduits) of glands (like sweat, mammary, and salivary glands). Their structure helps maintain the shape and integrity of the duct while allowing materials (sweat, milk, saliva, etc.) to pass through the lumen without the duct collapsing or leaking.

Locations: Ducts of mammary, sweat, and salivary glands, pancreatic ducts; also developing ovarian follicles and seminiferous tubules.

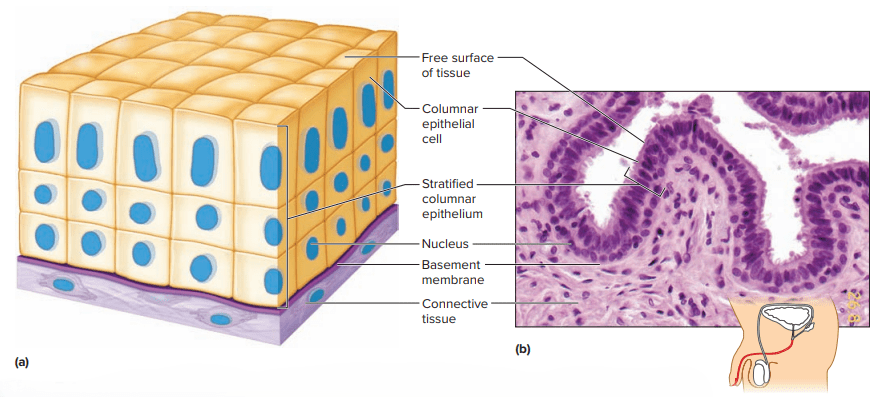

7) Stratified Columnar Epithelium

Structure: Several layers where the superficial cells are columnar and the basal layers are cuboidal.

Function: Adds protection where a tough lining is required with a columnar surface. The columnar surface allows for specialized functions like limited secretion or absorption while still giving the tissue structural strength from the extra layers. It’s used in places that need both a protective barrier against mechanical or chemical stress and a functional surface with the height of columnar cells for certain tasks.

Location: Stratified columnar epithelium is rare in the body. It’s found in select areas like parts of the male urethra, some large ducts of exocrine glands, and small regions at epithelial junctions where different tissue types meet.

Lab hint: Focus on the layered architecture when identifying.

8) Transitional Epithelium (Urothelium)

Structure: Multiple layers that change shape with stretch; cells look irregular when relaxed and become thinner/elongated when the organ fills (this results in the cell stretches).

Function: Expandable, leak-resistant lining; prevents urine contents from diffusing back into tissues.

Locations: Urinary bladder, ureters, superior urethra.

Key feature: Dome-shaped umbrella cells on the surface when relaxed; flattened when distended.

Glands: Epithelia That Secrete

Glands are organized collections of epithelial cells that are specialized for secretion. The two major categories of glands include:

- Exocrine glands – deliver products to surface ducts (e.g., skin, gastrointestinal tract lumen)

- Endocrine glands – release products (usually hormones) into tissue fluid or blood

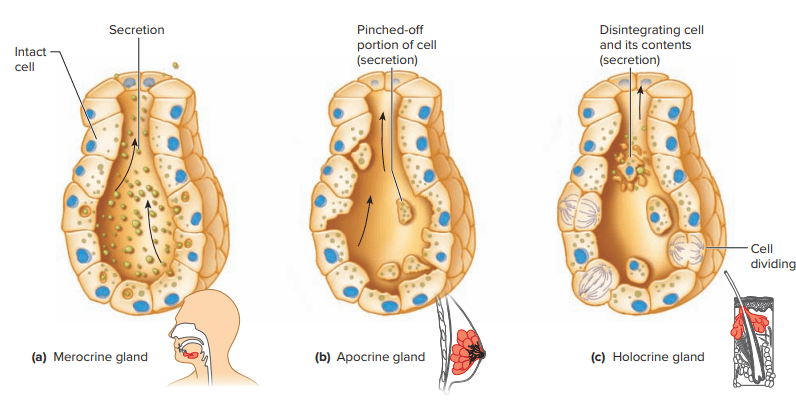

How Exocrine Glands Release Their Products

Merocrine (eccrine) Secretion: Most common secretion mechanism where products released by exocytosis.

- How it works:

- The gland’s product is packaged inside vesicles within the cell.

- The vesicles fuse with the cell membrane and release their contents into a duct or onto a surface by exocytosis.

- The cell remains intact—no part of it is lost during secretion.

- Key points:

- It’s the most common type of exocrine secretion in the body.

- Examples include:

- Sweat glands (eccrine type) producing watery sweat

- Salivary glands releasing saliva

- Pancreatic glands releasing digestive enzymes

- Think of it as the “cleanest” secretion method—the cell just ships out its product without damaging itself, so it can keep producing continuously.

Apocrine Secretion: The apical portion of the cell pinches off, releasing product with a bit of cytoplasm.

- How it works:

- The product builds up in the apical (top) portion of the cell.

- That top portion of the cell pinches off, carrying the secretion with it.

- The remaining cell repairs itself and continues producing more product.

- Key points:

- This method removes part of the cell’s cytoplasm along with the secretion.

- It’s less common than merocrine secretion.

- Examples include:

- Apocrine sweat glands in the armpits and groin (which become active at puberty)

- Mammary glands (which release milk fat in this way)

- Think of apocrine secretion as the cell “taking a little off the top”—it sends off its product along with a bit of itself.

Holocrine Secretion: The entire cell disintegrates, releasing accumulated product

- How it works:

- The gland cell fills up with its product (like oil or other secretions).

- Instead of just releasing the product, the entire cell breaks down and disintegrates.

- The cell’s contents—including the secretion—are released into the duct.

- New cells from deeper layers of the gland replace the destroyed cells.

- Key points:

- This method destroys the secreting cell each time it releases product.

- It’s less efficient in cell survival but allows for thick, oily secretions.

- Examples include:

- Sebaceous (oil) glands of the skin that produce sebum

- Certain tarsal glands in the eyelids

- You can think of holocrine secretion as a “cell suicide mission”—the cell dies in the process of delivering its product.

What Exocrine Glands Secrete

- Serous fluid: Watery, slippery, ideal for lubrication (notably along visceral and parietal membranes in thoracic and abdominopelvic cavities).

- Mucus: Thicker secretion that serous fluid and is rich in mucin (a glycoprotein). Goblet and mucous cells produce mucus throughout the digestive, respiratory, and reproductive tracts to protect underlying tissue and to aid in the movement of substances.

How to Recognize Epithelia in Practice

1) Start at the surface. Is there a free (apical) surface facing a space (lumen) or external environment? If yes, you’re probably looking at epithelium.

2) Count the layers (carefully).

- Single layer: simple

- Multiple layers: stratified

- Looks layered but every cell touches the base: pseudostratified

3) Judge cell shape at the surface. This is how stratified epithelia get their name (squamous/cuboidal/columnar).

4) Look for special features.

- Cilia (movement), microvilli (absorption), goblet cells (mucus)

- Keratinized surface (skin) vs. moist nonkeratinized lining (mouth, esophagus, vagina, anal canal)

5) Consider organ context and 3D orientation. Ask what kind of tube or surface you are cutting through. Also keep in mind that oblique vs. longitudinal sections can change the appearance of tissue dramatically.

Beyond Epithelium: The Other Three Tissue Types

- Connective tissue: Sits beneath most epithelia, contains blood vessels, and provides support, binding, and cushioning (think loose areolar tissue, adipose, cartilage, bone, blood).

- Muscle tissue: Skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle convert chemical energy into force and motion. Muscle tissue are involved in body functions ranging from walking to peristalsis to heartbeat.

- Nervous tissue: Neurons and glia enable rapid signaling, integrating and coordinating body activities.

Epithelium often works on top of connective tissue, adjacent to muscle (in organ walls), and are under neural control. This is an important reminder that tissues are partners in ensuring that the body is functioning properly.

Final Thoughts

In summary, epithelial tissues form the body’s avascular, high-turnover, and tightly packed barriers, expertly designed for protection, secretion, absorption, and excretion. Their classification, which is based on cell shape and layering, not only gives them their names but also hints at their specialized roles. Surface features like cilia, microvilli, and goblet cells serve as visible markers of their functions, from moving particles to maximizing absorption and producing protective mucus. Some epithelia, like transitional epithelium, offer unique adaptations, stretching and sealing to meet the demands of the urinary tract. Even glands, whether releasing watery secretions or oily products, trace their origins back to these versatile tissues; this underscores the central role epithelium plays in maintaining the body’s structure and function!

Source Used: Welsh, C., & Prentice-Craver, C. (2023). Tissues (Chap. 5, pp. 103–111). In Hole’s essentials of human anatomy & physiology (16th ed.). McGraw Hill.