We’ve now followed oxygen’s journey from the nose to the alveoli, where it enters the bloodstream and carbon dioxide exits. But we haven’t yet explored the powerful mechanisms and protective structures that make this exchange possible. Breathing isn’t just about lungs—it’s about muscles, bones, membranes, and pressure gradients, all working in harmony to keep air moving in and out of your body.

Let’s take a look at the thoracic structures that house and guard the lungs, then dive into the remarkable mechanics behind how we breathe.

The Thoracic Cavity: The Lungs’ Protective Shell

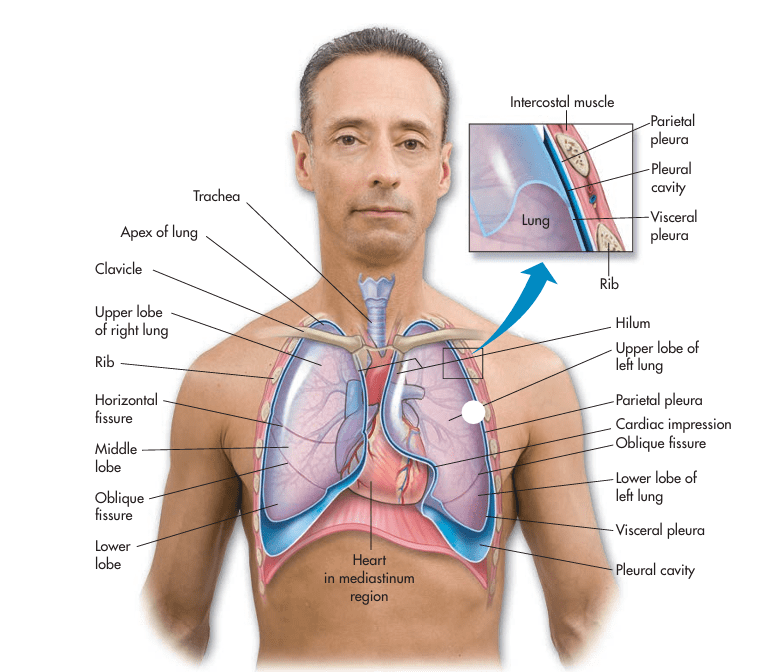

Your lungs sit in the thoracic cavity, a well-protected space surrounded by the rib cage, spine, sternum, and diaphragm. Sandwiched between the lungs is the mediastinum, which holds essential structures like the heart, esophagus, trachea, and major blood vessels.

To reduce friction during breathing, each lung is wrapped in a serous membrane called the pleura, composed of two layers:

- Visceral pleura: covers the surface of each lung.

- Parietal pleura: lines the inside of the thoracic wall and diaphragm.

Between these two layers is the intrapleural space, filled with a thin layer of pleural fluid. This fluid acts like biological lubricant, reducing friction as the lungs expand and contract. It also helps the lungs adhere to the chest wall via surface tension—critical for maintaining lung inflation.

The Right vs. Left Lung: A Tale of Two Lobes

- The right lung has three lobes (upper, middle, lower), separated by the horizontal and oblique fissures.

- The left lung has only two lobes (upper and lower), divided by the oblique fissure.

Why the difference? The left lung makes room for the heart, which sits slightly left of center in the chest cavity. This indentation in the left lung is known as the cardiac impression.

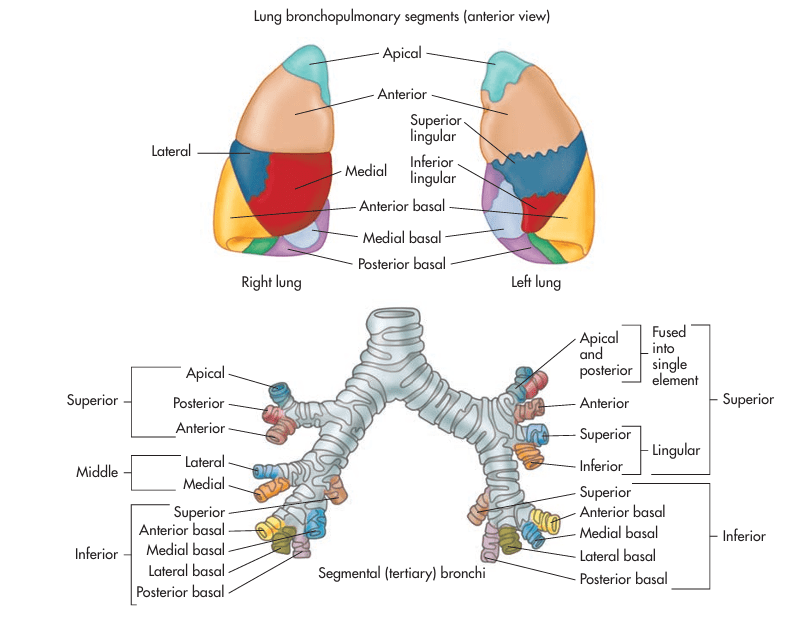

Each lobe is further divided into bronchopulmonary segments, each served by its own segmental bronchus and blood supply. This allows for surgical removal of diseased segments without impacting the function of the remaining lung.

The Rib Cage and Sternum: Bony Protection with Flexibility

Your rib cage consists of 12 pairs of ribs:

- True ribs (1–7): attach directly to the sternum via costal cartilage.

- False ribs (8–10): connect indirectly through the cartilage of the rib above.

- Floating ribs (11–12): have no anterior attachment.

The sternum, or breastbone, is divided into three parts:

- Manubrium (top)

- Body (middle)

- Xiphoid process (bottom)

These bones do more than protect vital organs—they also expand and contract to assist with ventilation. The flexible costal cartilage between ribs and sternum allows the rib cage to move during breathing.

How We Breathe: The Physics of Pulmonary Ventilation

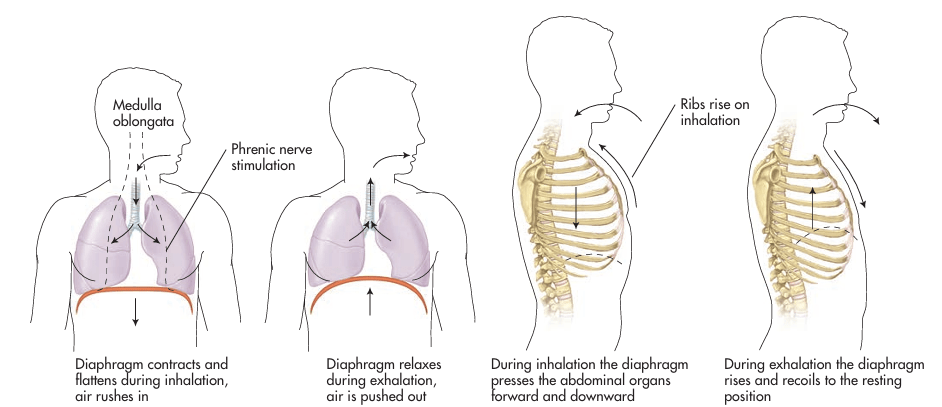

Breathing is driven by pressure differences between the atmosphere and your lungs. According to Boyle’s Law, when the volume of a space increases, the pressure inside decreases—and vice versa.

Inhalation (Inspiration)

- The diaphragm contracts and flattens, moving downward.

- The external intercostal muscles lift the ribs upward and outward.

- These actions increase the volume of the thoracic cavity.

- As volume increases, intrapulmonary pressure drops below atmospheric pressure, drawing air into the lungs.

Exhalation (Expiration)

- Normally a passive process.

- The diaphragm relaxes, forming its dome shape.

- The ribs recoil back to their resting position.

- This reduces thoracic volume, increasing intrapulmonary pressure and pushing air out.

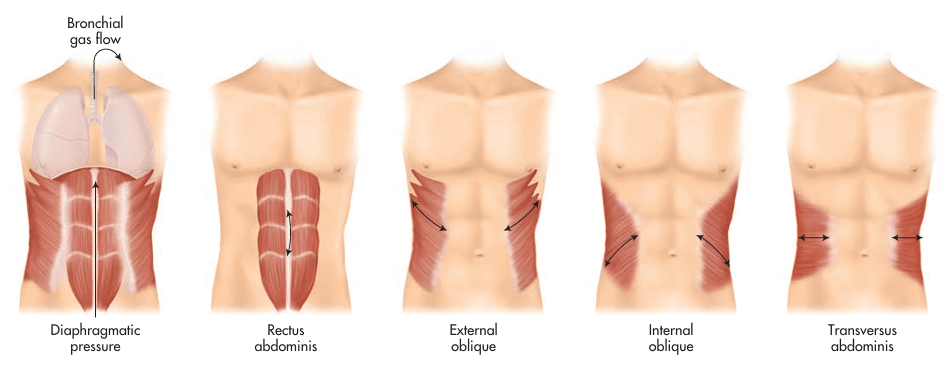

When Breathing Gets Tough: Accessory Muscles Step In

During exercise or in respiratory distress, your body recruits accessory muscles to help with breathing.

Inspiration Accessory Muscles:

- Sternocleidomastoid: elevates the sternum.

- Scalene muscles: raise the first two ribs.

- Pectoralis major and minor: lift the rib cage when arms are braced.

Expiration Accessory Muscles:

- Abdominal muscles (rectus abdominis, obliques): push the diaphragm up.

- Internal intercostals and latissimus dorsi: compress the thoracic cavity.

These muscles create forceful exhalation, like when blowing out candles, coughing, or running.

Lung Compliance: The Ease of Inflation

Compliance refers to the lung’s ability to stretch and expand.

- High compliance = lungs inflate easily (e.g., in emphysema)

- Low compliance = lungs resist expansion (e.g., in pulmonary fibrosis or ARDS)

Diseases that reduce surfactant production (such as in premature infants) or stiffen the lung tissue will lower compliance, making it more difficult—and more energy-intensive—to breathe.

Regulation of Breathing: Controlled by Chemistry and the Brain

The medulla oblongata and pons in the brainstem form the respiratory control center, sending rhythmic signals to breathing muscles. This system automatically adjusts based on blood chemistry.

- Rising CO₂ levels trigger increased breathing rate and depth to blow off excess carbon dioxide.

- Chemoreceptors in the aorta, carotid arteries, and medulla monitor blood pH, which is linked to CO₂ levels via the bicarbonate buffer system.

When blood becomes too acidic (low pH), respiration increases. When it becomes too alkaline (high pH), breathing slows.

Fun Fact: Why Mosquitoes Love Breath and Exercise

Did you know mosquitoes are attracted to carbon dioxide? When you exhale, you release CO₂—especially after a workout, when you’re also sweating and warm. These cues help mosquitoes find you even in the dark. So next time you’re hiking or camping, remember: your lungs may be helping the bugs track you!

Wrapping Up: Breath Is Movement, Protection, and Precision

From the pleura that cushion each lung, to the muscles and bones that drive ventilation, your respiratory system is a blend of structure and function. Each breath is made possible by expanding volumes, shifting pressures, and orchestrated muscle contractions. And it’s all regulated without you having to think about it—unless something goes wrong.

Understanding the anatomy and mechanics behind breathing helps us appreciate the miracle that happens every few seconds. Whether you’re sprinting up stairs or resting quietly in bed, your body is constantly working to fuel every cell with oxygen and carry away its waste.

Blog Source: Colbert, B. (2019). Chapter 14: The Respiratory System. In Anatomy & Physiology for Health Professions: An Interactive Journey (4th ed., pp. 290–318). Pearson Education. **All information used to write this blog was learnt from this textbook chapter.