Welcome back to our deep dive into the respiratory system! In Part 1, we explored how your nose, pharynx, and larynx work together to warm, filter, and humidify the air you breathe. Now, we descend further into the lungs, tracing the path of oxygen from your throat to the smallest air sacs in your body. This is where gas exchange—perhaps the most critical function for sustaining life—takes place. The journey through your lower respiratory tract goes from macro to microscopic!

The Tracheobronchial Tree: A Highway Built for Airflow

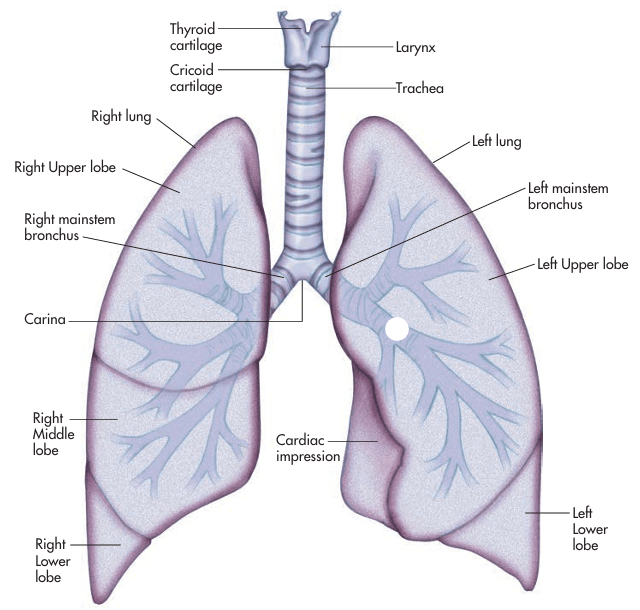

After passing through the vocal cords in the larynx, air enters the trachea, a sturdy tube about 4–5 inches long that runs down the front of your neck into your chest. Its structure is reinforced by 16 to 20 C-shaped cartilage rings, which prevent the trachea from collapsing and allow flexibility for swallowing. The open portion of each “C” faces the esophagus, giving food a soft pathway during meals.

As the trachea descends, it splits at the carina, an important anatomical landmark, into the right and left mainstem bronchi—each leading into its respective lung. This marks the start of the bronchial tree, a system of increasingly smaller and more numerous airways that resemble the branching of an upside-down tree.

Here’s a breakdown of the branching:

- Primary (mainstem) bronchi: one per lung

- Secondary (lobar) bronchi: one per lung lobe (three on the right, two on the left)

- Tertiary (segmental) bronchi: one per bronchopulmonary segment (10 in the right lung, 8–9 in the left)

As these airways branch deeper, they become narrower, the cartilage thins and eventually disappears, and the epithelium transitions from columnar to cuboidal in shape. By the time we reach the bronchioles, we’ve entered the flexible, muscular part of the airway tree that controls airflow through smooth muscle contraction.

The Terminal Bronchioles is the Gateway to Gas Exchange

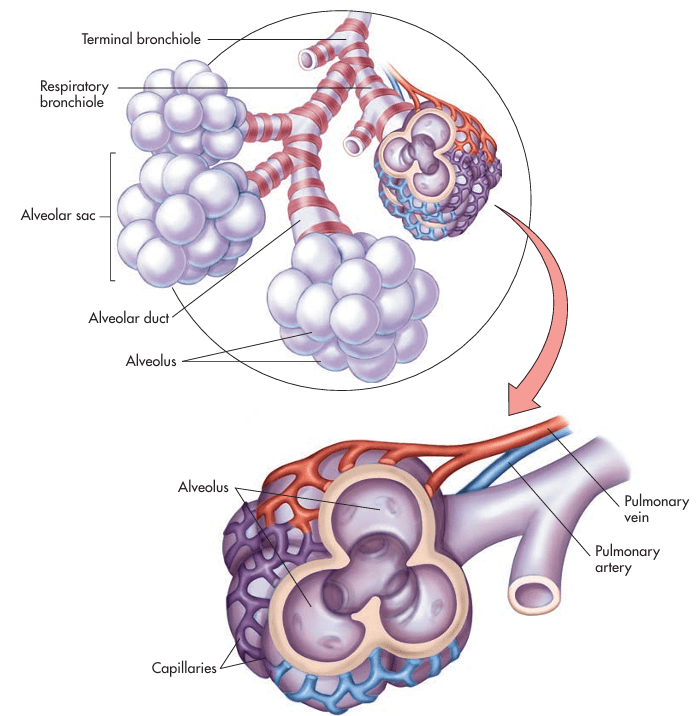

The terminal bronchioles, typically only 0.5 mm in diameter, represent the last stop in the conducting zone—the part of the respiratory system responsible solely for transporting air. These bronchioles no longer have cartilage, goblet cells, or mucus-secreting glands. Instead, they feature ciliated cuboidal epithelium and thin walls designed to pass air efficiently into the next zone.

Just beyond the terminal bronchioles are the respiratory bronchioles, the beginning of the respiratory zone, where limited gas exchange starts to occur. From here, we enter a network of alveolar ducts, which open into clusters of alveoli known as alveolar sacs.

Alveoli: The Engine Room of Respiration

The alveoli are where it all happens—the site of external respiration, where oxygen enters the bloodstream and carbon dioxide leaves it. Each alveolus is a microscopic air sac about 200 microns in diameter, surrounded by a dense network of pulmonary capillaries. Together, the alveoli and capillaries form the alveolar-capillary (or respiratory) membrane, a structure so thin—just 0.004 mm—that it allows rapid gas exchange by simple diffusion.

Each adult lung contains around 300 to 600 million alveoli, creating an enormous surface area—about 750 square feet, roughly the size of a tennis court. This massive surface area is vital: the more surface you have, the more gas you can exchange.

The Four-Layer Alveolar-Capillary Membrane

Oxygen and carbon dioxide must cross four microscopic layers to move between the lungs and blood:

- Surfactant layer – A phospholipid substance secreted by Type II pneumocytes. It reduces surface tension, preventing the alveoli from collapsing on themselves during exhalation.

- Alveolar epithelium – Lined mostly by Type I pneumocytes, which are extremely thin to facilitate diffusion.

- Interstitial space – A tiny gap containing connective tissue and interstitial fluid. If fluid builds up here (as in pulmonary edema), gas exchange becomes impaired.

- Capillary endothelium – The thin inner lining of the blood vessel through which oxygen enters red blood cells.

The Alveolar Cell Types

Three specialized cell types populate the alveoli:

- Type I pneumocytes: Flat, scale-like cells that form the structural wall of the alveolus and enable gas exchange.

- Type II pneumocytes: Cuboidal cells that produce surfactant and participate in repair if Type I cells are damaged.

- Alveolar macrophages (Type III cells): Immune cells that roam the alveolar space, engulfing debris, bacteria, and particles to keep the lungs clean and infection-free.

Additionally, small pores between alveoli, called pores of Kohn, allow macrophages to move from one alveolus to another and help equalize pressure between alveoli.

What Happens When Gas Exchange Fails?

When the alveolar-capillary membrane is damaged, thickened, or obstructed, the consequences can be serious:

- Pneumonia fills alveoli with fluid and pus, blocking oxygen.

- Pulmonary fibrosis thickens the interstitial space, slowing gas exchange.

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) disrupts surfactant production, leading to alveolar collapse.

In all these cases, arterial blood gases (ABGs) are measured to assess oxygen (PaO₂) and carbon dioxide (PaCO₂) levels in the blood. A low PaO₂ or a rising PaCO₂ can indicate impaired respiratory function.

The Role of Hemoglobin and Red Blood Cells

Inside the capillaries, red blood cells (RBCs) pick up oxygen and release carbon dioxide. The oxygen binds to hemoglobin, a protein made of iron-rich subunits. Each red blood cell carries about 280 million hemoglobin molecules, and each hemoglobin can carry up to four oxygen molecules.

Oxygen-rich blood leaves the lungs and returns to the left side of the heart, which then pumps it throughout the body. The right side of the heart, in turn, sends oxygen-poor blood back to the lungs to repeat the cycle.

If iron levels are low—such as in iron-deficiency anemia—less oxygen can be transported, which leads to fatigue and weakness. To compensate, the body may produce more RBCs through a hormone called erythropoietin, secreted by the kidneys in response to low oxygen levels.

Wrapping Up: Life Begins Where Air Meets Blood

The lower respiratory tract is a masterpiece of design, optimized for efficient airflow, precise branching, and massive surface area. Every breath you take is a symphony of pressure, diffusion, and cellular coordination, ending with a microscopic handoff between alveolus and blood vessel. But this system is fragile, too. A thin layer of fluid, a slight thickening of membranes, or a drop in surfactant can jeopardize the body’s most essential exchange.

In Part 3 of this blog series on the Respiratory System, we’ll step back from the microscopic world to explore how breathing actually happens. How does air get in and out? What muscles are involved? And what happens when we take that first breath—or our last?

Blog Source: Colbert, B. (2019). Chapter 14: The Respiratory System. In Anatomy & Physiology for Health Professions: An Interactive Journey (4th ed., pp. 290–318). Pearson Education.