The immune system is constantly on guard, ready to combat an array of potential threats. At the heart of this defense lies the innate immune system, which serves as the body’s first line of protection against infections. Among its key players are macrophages, highly versatile phagocytic cells that act as sentinels, capable of detecting and responding to invading pathogens with remarkable precision.

Macrophages achieve this by leveraging specialized receptors on their surfaces, designed to recognize molecular patterns unique to microbes—patterns absent in human cells. These pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) enable macrophages to distinguish between “self” and “non-self,” allowing them to identify foreign invaders and swiftly initiate an immune response.

This article delves into the mechanisms by which macrophages recognize pathogens, the roles of specific receptors such as glucan, mannose, and Toll-like receptors (TLRs), and how these cells activate robust immune responses even in the absence of T cell involvement. Understanding these processes offers a deeper appreciation of the innate immune system’s sophistication and its critical role in safeguarding the body.

How Macrophages Recognize Pathogens and Activate the Immune Response

The innate immune system relies on specialized cells, such as macrophages, to detect and respond to invading pathogens. These phagocytic cells are equipped with surface receptors that recognize specific molecular patterns, known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which are unique to microbes and absent in human cells. This ability to differentiate between “self” and “non-self” forms the foundation of innate immunity.

Recognizing Pathogens Through Specific Receptors

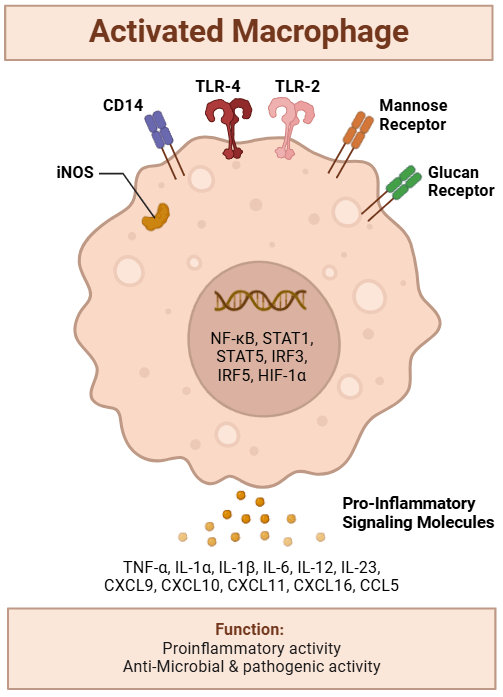

Macrophages are armed with a variety of receptors that recognize distinct motifs found on bacterial and viral surfaces. These receptors allow macrophages to detect the presence of infection and initiate an immune response. These receptors include:

- Glucan Receptors

- Bacteria have high levels of glucan (a chain of glucose molecules) in their cell walls, a feature absent in human cells.

- Macrophages possess glucan receptors that bind to glucan, enabling them to identify the presence of bacteria.

- Once a glucan receptor binds to glucan on a bacterial cell, the macrophage recognizes the foreign invader and activates its immune response.

- Mannose Receptors

- Mannose is a sugar commonly found on the surfaces of bacteria but is absent in human cells.

- Macrophages express mannose receptors that specifically recognize and bind to mannose, triggering macrophage activation.

- CD14 and Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4)

- Gram-negative bacteria contain lipopolysaccharide (LPS) on their surfaces.

- CD14, a receptor on macrophages, binds to LPS and interacts with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), which then activates the macrophage.

- This interaction triggers a cascade of intracellular signaling events, leading to the production of cytokines and chemokines that recruit additional immune cells and amplify the immune response.

The Discovery of Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs)

Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs), critical components of innate immunity, were first discovered in fruit flies. Researchers found that knocking out the TLR gene in fruit flies resulted in massive fungal infections, demonstrating the receptor’s vital role in immune defense. This discovery prompted the identification of human TLRs, which play a similar role in detecting and responding to infections.

Each TLR is highly specific to certain microbial molecules. For example, TLR9, an extracellular receptor, recognizes CpG DNA, which is abundant on viruses. On the other hand, some TLRs are located within cells and can detect viral components, enabling them to activate immune responses during viral infections. These intracellular TLRs can stimulate the production of interferon-alpha (INF-α), which helps cells protect themselves from viral replication.

Macrophage Activation Without T Cells

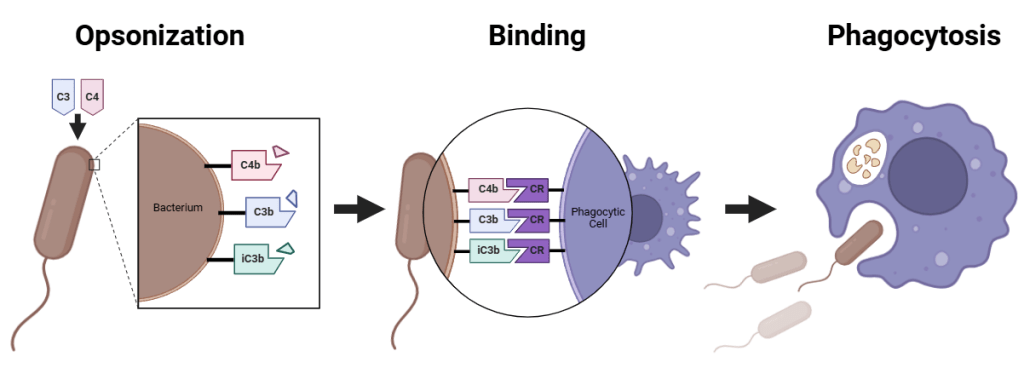

Macrophages can initiate an immune response independently of T cells. When a bacterial PAMP binds to its corresponding receptor on the macrophage, such as mannose or glucan receptors, the macrophage becomes activated. This triggers:

- Cytokine and Chemokine Release: The macrophage secretes signaling molecules that recruit additional immune cells to the site of infection.

- Enhanced Phagocytosis: The macrophage increases its ability to engulf and destroy pathogens by forming phagolysosomes, which merge to kill the ingested bacteria.

For example, the binding of LPS to CD14 on macrophages, and its subsequent interaction with TLR4, activates the transcription factor NF-κB. This transcription factor turns on macrophage genes responsible for producing cytokines and chemokines, intensifying the immune response.

Redundancy in Pathogen Recognition

While TLRs are essential for immune activation, macrophages also rely on other receptors, such as mannose and glucan receptors, to detect pathogens. These receptors ensure that macrophages can identify foreign substances even if TLR function is compromised. However, the absence of functional TLRs would reduce the efficiency of pathogen recognition and immune activation.

Beyond Bacterial Infections

While many TLRs focus on bacterial components, others are tailored to detect viral infections. For instance, TLRs inside cells can recognize viral DNA or RNA, activating mechanisms to combat the infection. This highlights the innate immune system’s ability to respond to both extracellular and intracellular threats.

Conclusion

Macrophages are versatile and critical players in the innate immune response, equipped with an array of receptors that recognize unique microbial patterns. Through these receptors, macrophages can detect pathogens, activate immune responses, and protect tissues from infection—even in the absence of T cell involvement. The redundancy and diversity of these receptors underscore the robustness of the innate immune system in defending against a wide range of microbial threats.

In our next Immunology Blog, we will discuss the role of TLRs in HIV disease progression!