In the complex world of immunology, antigen recognition molecules play a crucial role in identifying and responding to pathogens. These molecules are structured with two distinct components that each contribute to their function. The first component, known as the variable regions, serves as the specific antigen binding sites, allowing the immune system to target a diverse range of antigens. Complementing this, the second component is the constant region, which is responsible for the effector functions necessary for mounting an immune response. To ensure consistency and effectiveness within a given category of antigen recognition molecules, the constant region is designed to be uniform, providing a reliable mechanism for immune responses.

The immune system comprises two main categories of antigen recognition molecules: antibodies (also known as immunoglobulins) and T-cell receptors. While both classes serve the same fundamental function—recognizing antigens—their mechanisms for doing so are entirely different. The sequences of the variable regions in immunoglobulins and T-cell receptors show no similarity, as they are distinct proteins. Nevertheless, both variable regions exhibit high levels of specificity, which is crucial given their role as antigen-binding sites.

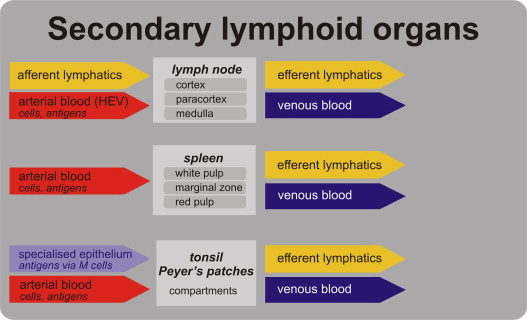

The immune system is organized according to anatomical locations. Let’s begin with T-cells. All T-cell receptors are produced in the thymus, a primary lymphoid tissue. These receptors cannot exit the thymus until all self-reactive T-cells have been removed. Self-reactive T-cells are identified by their surface receptors, which bind to self (non-foreign) antigens. If not eliminated, these self-reactive T-cells could attack the body’s own tissues and proteins, leading to autoimmune diseases. In contrast, B-cell receptors are generated in the bone marrow, another primary lymphoid tissue. Similar to T-cells, B-cell receptors must remain in the bone marrow until all self-reactive B-cells have been eliminated. After self-reactive lymphocytes are eliminated, the remaining lymphocytes leave the primary lymphoid tissues and enter the secondary lymphoid tissues, which include the lymph nodes and spleen. In these secondary sites, the lymphocytes await the presence of their specific antigen. If that antigen enters the body, the immune response is triggered, leading to the activation and proliferation of the corresponding B and T cells.

The lymph node is anatomically organized, with B cells situated in the cortical region, just outside the lymph node’s core. Upon stimulation by their specific antigen, B cells undergo proliferation, forming a germinal center—a dense cluster of clonal cells. These B cells remain in the lymph node, where they produce antibodies, the effector molecules that help combat infections. The antibodies then enter the bloodstream to fight off the infection. In contrast, once T cells are activated by recognizing their specific antigen, they leave the lymph node and migrate into the peripheral blood. There, they directly combat the infection using their surface receptors. If a B or T cell does not encounter the antigen it is pre-programmed to recognize, it may migrate to a different lymph node. There, these cells will continue to wait for their specific antigen. In practice, most of these cells will never encounter their target antigen and will undergo apoptosis at the end of their lifespan. Meanwhile, new copies of these specific T and B cells are generated to replace the old ones. Although the spleen functions similarly to the lymph nodes, it differs structurally, with distinct regions where T and B cells are localized. In the spleen’s architecture, regions containing M cells allow antigens to pass through. B cells are primarily located in the germinal centers and follicles, while T cells are positioned around the B cells. Upon activation, T cells exit through the efferent lymphatics and enter the bloodstream. B cells, on the other hand, secrete the antibody IgA, which then crosses the epithelium into the lumen of adjacent blood vessels to combat the pathogen.

Our fun fact for today’s blog is that CD4+ T-cells are the most common lymphocytes in the circulating blood! In our next Immunology Blog, we will discuss the how B and T cells recognize different antigen contexts!