Lymphocytes, consisting of T-Cell, B-Cell, and Natural Killer Cells, are the attacking force of the acquired/adaptive immune system. Their overarching function is to selectively target and eliminate a wide variety of invading pathogens. Now, you may be wondering what exactly is the process that enables T-Cells and B-Cells to successfully eliminate different foreign bodies. The answer lies in ligand-receptor binding.

To begin, let’s define and discuss a few key terms. An antigen is something that the immune system can recognize (usually a protein). On the other hand, an immunogen is anything that can generate an immune response. Immunogens are a more selective group than antigens, as immunogens are substances that are strong enough to generate T & B cell proliferation. As such, all immunogens are antigens but NOT all antigens are immunogens. This is because some antigens are not strong enough to generate an immune response. This specific characteristic is utilized in vaccine design where scientists utilize antigens that aren’t usually strong enough to generate an immune response to bolster the immune system of the human recipient. This approach gradually trains the immune system to recognize a pathogen while also preventing serious infections and subsequent immune responses.

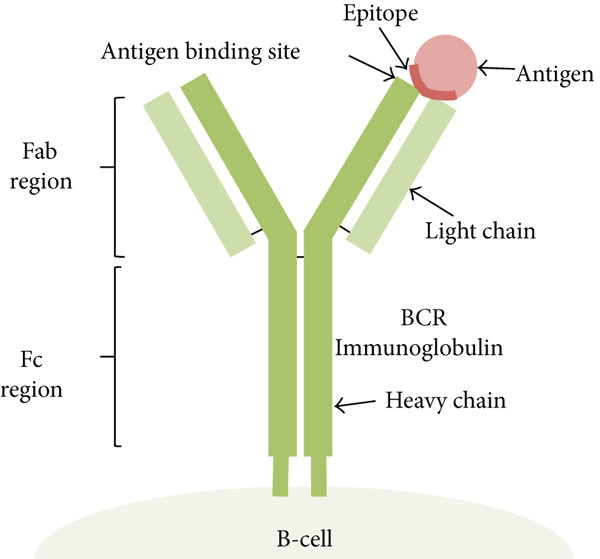

Let’s further explore the pivotal structure of an antigen. Within an antigen, there are small regions called epitopes. Epitopes are the smallest unit that an immune response can recognize. There are hundreds of epitopes in a single antigen and each one of these epitopes can be identified by different antibodies or receptors. Sometimes, recognizing one epitope can be a good way to recognize the antigen and eliminate it, while recognizing another epitope may not be the best way to specifically identify and target the pathogen. This concept can determine why one person’s immune response may be worse than other’s as that person’s lymphocytes are recognizing a different epitope on the antigen of their pathogen rather than the best one. Another important thing to remember is that our immune systems can recognize a wide variety of epitopes.

The process behind the immune response is logical. When your body is first exposed to antigen A, there is a lag period where your body isn’t making any antibodies. In this time period, your body is preparing a targeted immune response where is develops the correct receptor/antibody to fight off antigen A (indicative of an invading pathogen). But after a week, you start mass-producing the corresponding antibody to antigen A. As you clear the pathogen, the antibody response goes down. Let’s say, that weeks/months later, you are exposed to antigen A again, but also antigen B at the same time (ex: getting a cold at the same time you were exposed to chicken pox). Now, you will have a rapid response to antigen A (the antigen you were previously exposed to) with no lag time. This means that within a day or 2, you have rapid increases in your antibody response as you are reaching antibody production level that is 1000s of times higher than from your first exposure. On the other hand, your immune response to antigen B has a lag time, since you have never been exposed to it before. After that week of a lag, antibodies and receptors corresponding to antigen B are mass produced, initiating a combative immune response. This example explains the hallmark of the immune system. The first time you are infected with something, you are horribly sick because in that one week lag period, antibodies aren’t created. Therefore, there is no significant defense that can specifically target the invading pathogen, so the pathogen uses this opportunity to proliferate, resulting in an infection. The next time you are exposed to that same antigen (same exact pathogen), you don’t get infected again because as soon as your body recognizes that same pathogen, you have a rapid ramping up and activation of the immune response eliminating the virus before it gets the change to infect.

What’s interesting is that scientific technology utilizes this same immune concept. Prime examples of this are vaccines. Instead of letting you get infected and suffer from sickness to educate your immune system, vaccines do the exact same thing as “first time infection” but instead use an attenuated/dead virus to ensure that you have antibodies and receptors on T cells that will target the virus (antigen) without the infection component. An attenuated virus is better than a dead virus for vaccine usage because an attenuated virus is more like the real virus. Therefore, there will be greater T cell proliferation because you are getting a real infection, resulting in more memory cells being stored throughout the body and longer lasting effects.

Here is the breakdown of the approximate time spans that exposure to a dead, attenuated, and live pathogen (infection) provide you with immunity:

- If you were vaccinated with a dead virus, you are immune to this virus for ~ 10-20 years

- If you were vaccinated with an attenuated virus, you are immune to this virus for ~ 20-23 years

- If you were actually infected by the live virus, you are immune to this virus for the rest of your life

Even before pathogen infiltration, your body creates/has thousands of different types of T cells, each recognizing a different antigen. For instance, you may have only one T-cell that recognizes the varicella-zoster antigen (chickenpox). Now, during a chicken pox infection, you need to proliferate that specific T-cell to initiate an immune response. This results in millions of these chicken pox specific T cells. With this sheer number of activated T cells in the effector (or combative) phase, you clear the infection. What’s crucial to remember is that after your chicken pox infection, you don’t get rid of all these specific T cells. Instead, since you now have one cell that successfully recognizes and eliminates the chicken pox antigen, you keep thousands of these cells as memory cells stored in lymph nodes and costal tissue throughout your body. When your body next recognizes the same chicken pox antigen infiltrating your body, instead of having to start from very few specific T-cells and then expanding that population, which is a time-consuming process, now you already have millions of these T cells all distributed throughout the body that are ready to rapidly mount an immune response. This is why the second time you see an antigen, there is a much more dramatic and quick response.

In our next Immunology Blog, we will discuss the different types of antigen recognition molecules that the immune system employs to efficiently eliminate foreign invaders!