The immune system showcases a diverse array of specialized cells, each with distinct functions, capabilities, and specificities. What many may not realize is that all of these immune cells originate from a single type of cell—the hematopoietic stem cell. The normal differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells occurs in three main steps:

- Starting as pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells, this single cell type has the potential to become any type of cell.

- Different stimuli, factors, and environmental signals determine the differentiation of pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells. This process makes differentiation dependent on both environment and associated stimuli. The presence of specific stimuli in particular environments leads to varying differentiation outcomes.

- Pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells differentiate into:

- Myeloid phagocytic cells

- Dendritic cells

- Lymphoid progenitor cells (which subsequently differentiate into B cells, T cells, NK cells, and effector cells).

It’s crucial to note that differentiation is a one-way street. Once a cell commits to becoming a specific type, such as a cytotoxic T cell, it cannot revert to being a lymphoid progenitor cell and then differentiate into a B cell. There is no reversal in immune cell differentiation. This differentiation process highlights how the immune system generates a vast array of specialized cells to defend against pathogens and maintain self-tolerance, all guided by environmental cues and stimuli.

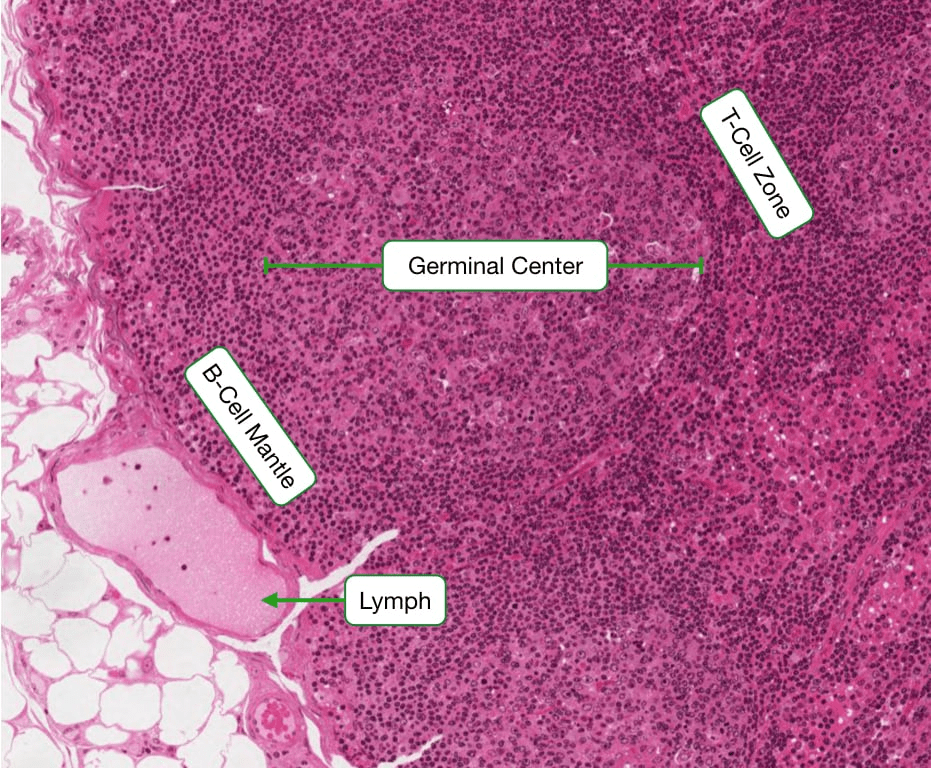

Histology is a vital tool for researchers to comprehend and visualize differences in immune function. It underscores the importance of visual observation in understanding cellular activities. Specifically, histology plays a crucial role in distinguishing between active and inactive lymphocytes. Inactive lymphocytes can be identified by their large nucleus and minimal cytoplasm. The scarcity of cytoplasm indicates that these white blood cells (WBCs) are currently inactive and not engaged in immune responses. Consequently, they lack major organelles except for a standard nucleus, highlighting the body’s efficient energy management. Why should our bodies maintain inactive T or B cells, primed to recognize and respond to foreign substances if no immediate threat exists? The absence of cytoplasm or significant organelles reflects the immune system’s readiness state—cells remain dormant until triggered by danger signals. Histological examination further reveals that upon activation, lymphocytes undergo changes: organelles become activated, the nucleus shrinks, and there is a notable increase in endoplasmic reticulum (ER), RNA production, golgi apparatus, secretory proteins, and mitochondria. These changes signify heightened cellular activity and energy consumption required for transforming inactive lymphocytes into effector cells capable of mounting immune responses.

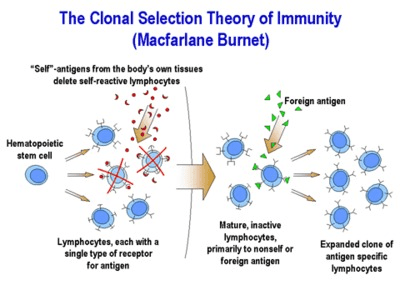

Having delved into the utility of histology and the differentiation pathways of immune cells, let’s explore why the immune system exhibits such remarkable specificity. This specificity is elucidated by the clonal selection hypothesis (CSH), which forms the foundation for understanding the function of the acquired immune system. According to the CSH, each lymphocyte possesses a single receptor that dictates its specificity towards a particular pathogen. For example, although a B cell or T cell may express thousands of immunoglobulin molecules or T cell receptors on its surface, all of these molecules are dedicated to recognizing the same antigen—a protein marker specific to the foreign invader. For instance, a T cell expresses thousands of T cell receptors, each uniquely programmed to recognize a specific pathogen. Therefore, a single T cell might recognize a peptide from HIV, meaning all the surface molecules of that T cell are geared towards detecting HIV. Conversely, another T cell might be primed to recognize antigens from chickenpox, so all its surface markers are specialized for chickenpox recognition. This system ensures that each immune response is finely tuned to combat a particular threat, demonstrating the immune system’s adaptive precision in targeting diverse pathogens.

This specificity begins with the interaction between a foreign molecule and a lymphocyte receptor capable of recognizing it. This interaction triggers activation of B and T cells, enabling them to initiate an immune response. As these activated lymphocytes proliferate, they replicate identically, producing a large number of cells that all target the same antigen recognized by the original activated cell. This process defines the immune response: generating numerous identical cells that are all geared towards combating the invaders. Simultaneously, it is crucial to eliminate lymphocytes that possess receptors for self-antigens. This system carries inherent risks, as an immune response mistakenly attacking self-antigens can lead to autoimmune diseases. Protective and regulatory mechanisms are in place to eliminate any self-reactive lymphocytes that may be generated. This intricate balance ensures that the immune system efficiently targets pathogens while avoiding harmful attacks on the body’s own tissues, illustrating the sophisticated regulatory mechanisms essential for immune function.

The Clonal Selection Hypothesis fundamentally revolves around the concept of single-cell, single-antigen recognition, which is central to the acquired immune response. This means that each proliferating cell inherits identical gene segments that encode for immunoglobulin molecules or T cell receptors. However, through extensive somatic gene rearrangements, each cell produces thousands of surface molecules that are specific to one particular pathogen antigen. For example, one cell might recognize Tuberculosis, while another, derived from the same pluripotent progenitor, recognizes a completely different pathogen antigen such as chickenpox. When these cells proliferate, their progeny retain the specificity of their parent cells, all targeting the same antigen. Somatic gene rearrangement is the critical process by which different T and B cells acquire their unique antigen specificity. This process underscores the adaptive nature of the immune system, where diverse pathogens can be recognized and targeted through a highly specialized and specific response mechanism.

Having discussed the clonal selection hypothesis, in the next Immunology Blog, we will discuss the process by which lymphocytes recognize and target a foreign invader with specificity!