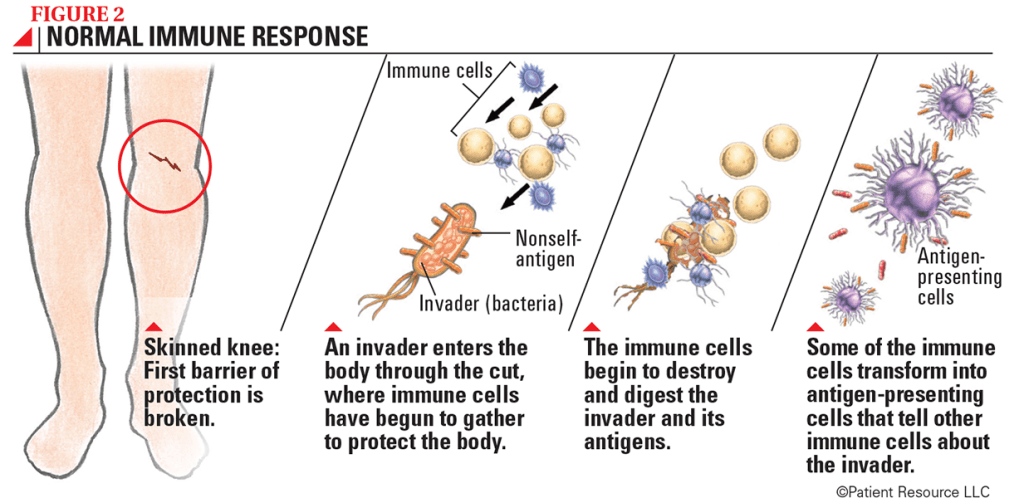

The immune system has one primary task: protecting the body by eliminating foreign pathogens while avoiding attacks on self. To fulfill this duty, the immune system must perform several critical functions:

- Differentiate between foreign and self, which means distinguishing invading pathogens from the body’s own tissues.

- Once the foreign invader is identified, amplify its recognition throughout the immune system so that other components can quickly respond to it.

- Recruit helper cells, mobilizing both innate and adaptive effector cells.

- Enable mobilized effector cells to eliminate and clear pathogens from the body.

- Prepare for future challenges and prevent recurring infections. This is a hallmark of the acquired immune system: after an initial infection, subsequent infections are either prevented entirely or manifest in milder forms. The immune system operates on the principle of “fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.”

For the immune system to effectively execute these tasks, it must possess:

- High sensitivity: The immune system must not only differentiate between infectious invading agents and non-infectious/self agents but also discern between different types of pathogens, such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi. This differentiation is crucial because various pathogens elicit distinct immune responses and necessitate specific effector molecules. Additionally, the immune system requires a high degree of specificity to recognize subtle variations in amino acid sequences, distinguishing between cellular and foreign proteins to target only the latter. This specificity extends to different biomolecules as well.

- Memory: Once infected for the first time, the immune system must retain crucial details about the invading species. This memory enables it to mount a quicker and more effective response upon encountering the pathogen again, minimizing the severity of illness.

- Ability to deactivate: Following the clearance of an infection, it is essential for the immune system to deactivate effector cells. Without an ongoing infection to combat, these potent cells must demobilize promptly. Failure to do so risks them attacking the body’s own tissues.

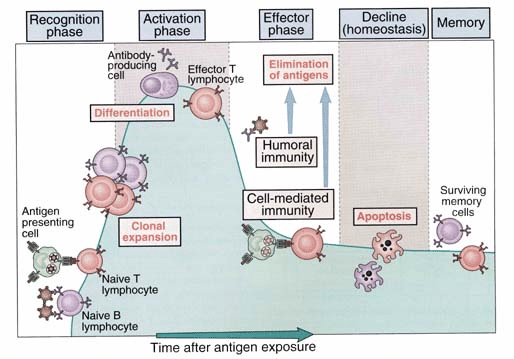

These attributes collectively empower the immune system to defend the body against pathogens while preserving its own tissues and functions. Having reviewed the requirements of a functional immune system, let’s explore the phases of immune activation and the initiation of an immune response. The process begins with the Cognitive Phase, during which an antigen—a recognizable protein sequence from a foreign body—binds to a receptor on a specific immune cell capable of recognizing it. The subsequent phase commences when the antigen binds to this specific immune cell, which is known as the Activation Phase. Upon binding, the immune cell becomes activated, which triggers either proliferation or differentiation. Crucially, the immune cell can differentiate into antigen-specific cells, such as B and T cells or transform into more potent phagocytic cells like macrophages. Finally, during the Effector Phase, the immune cells achieve full activation and readiness to mobilize a response aimed at eliminating the infection.

Through the immune response, the immune system protects the body against 4 classes of pathogens:

- Extracellular bacteria, parasites, & fungi

- Intracellular bacteria & parasites

- Viruses (intracellular)

- Parasitic worms (extracellular)

Extracellular pathogens reside outside the cell, circulating in the bloodstream and throughout the body. These pathogens encompass bacteria, parasites, fungi, and parasitic worms. They require a specific immune response tailored to targeting extracellular threats. The most effective immune defenses against extracellular pathogens are antibodies and complements, which operate as soluble factors in the extracellular environment. However, antibodies cannot penetrate cells. Therefore, when bacteria infiltrate cells and transform into intracellular pathogens, antibodies become ineffective in eliminating them. Intracellular pathogens, such as bacteria causing tuberculosis (TB), parasites, and viruses, are characterized by their presence inside host cells and the inability for antibodies to effectively eliminate them. Furthermore, unlike the previously discussed microscopic pathogens, parasitic worms are macroscopic entities requiring a distinct immune response. The challenge lies in confronting macroscopic worms with microscopic immune cells, which necessitates an entirely different strategy for effective defense.

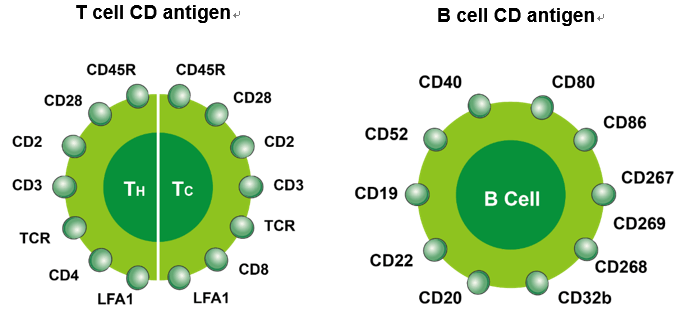

If you have any background in immunology, you’re likely aware that the field’s nomenclature and terminology can be extensive and confusing. Therefore, let’s clarify some fundamental immunological terms and their meanings. In immunology, the abbreviation CD is frequently used to denote different cell types, such as CD4+ or CD8+ T-cells. CD stands for “cluster of differentiation.” This designation arises because cells express distinct membrane proteins that are recognized by monoclonal antibodies, and these proteins define the unique pattern of cell-specific proteins present on their surface. These CD proteins are identified by sequential numbers, such as CD4+ or CD8+ T-cells. A CD4 cell corresponds to a helper T-cell, while a CD8 cell corresponds to a suppressor T-cell (also known as cytotoxic T-cell). These two CD numbers are among the most well-known, but there are over 320 identified CD proteins. Other common CD numbers include CD19, which denotes a B cell, and CD3, which identifies standard T cells.

In the next Immunology Blog, we will delve into a more detailed discussion of the differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells, as well as explore the clonal selection hypothesis.