World War I, known as the Great War, resulting in approximately 40 million deaths, marked a pivotal moment in our understanding of the significance of blood transfusions. The sudden loss of large volumes of blood, often due to acute traumas like gunshot wounds or amputations, is typically fatal. However, the practice of transfusing blood from a healthy individual, who can withstand the loss of 1-2 pints of blood, presents an opportunity to save the life of an injured or ill person. The concept behind blood transfusions is to provide the injured individual with healthy and functional red blood cells while allowing their own bone marrow time to replenish the loss of the initial self RBCs from bleeding.

The use of blood transfusions has become more prevalent, both in wartime scenarios and in everyday civilian life. However, not everyone can simply donate blood to a friend. Extreme caution must be exercised in blood transfusions, particularly ensuring compatibility between the blood of the donor and the recipient. Before World War I, scientists undertook the task of categorizing different blood groups, laying the groundwork for the blood grouping system that modern medicine relies on. To determine compatibility between donor and recipient blood, researchers conduct tests. This involves adding serum (blood plasma lacking fibrinogen) to the recipient’s red blood cells (RBCs) without causing them to clump together. If the recipient’s RBCs do clump, it could lead to their disintegration or the formation of clots that might block smaller capillaries, hindering proper blood flow to tissues and potentially causing illness in the recipient.

Four main groups of blood have been classified based on whether the RBCs from the clumping (agglutinating) test described above have one or another clumping/agglutinating factor, have no clumping factor, or have both clumping factors. These groups include:

- Group A – Has “A” agglutinating factor in RBCs and Anti-B factor in the serum

- Group B – Has “B” agglutinating factor in RBCs and Anti-A factor in the serum

- Group AB – Has both “A” and “B” agglutinating factors in RBCs, but none of the Anti-factors in the serum

- Group O – Has neither the “A” nor “B” agglutinating factors in the RBCs but both Anti-A and Anti-B factors in the serum

Individuals with blood types A, B, or AB can donate or receive blood from others with the same blood type. In emergencies, individuals with type O (group O) blood can donate to those with blood types A, B, or AB. This is because the red blood cells (RBCs) in group O blood lack A or B antigens on their surfaces. The significance of the Anti-A and Anti-B serum factors in the acceptance of foreign or non-self blood is outweighed by the presence of RBC factors. Consequently, successful blood transfusions can take place between blood types A/B/AB and group O. This is why individuals with group O blood are called the “universal donors.” Group O is also the most prevalent blood group in the human population.

Another agglutinating factor that is assessed before blood transfusions occur is the Rh factor, an antigen that can be found on RBCs. The Rh factor is named after the Rhesus monkey in which this Rh factor was first determined. Approximately 85% of all human beings have the Rh factor on their RBCs, and are considered to be Rh-positive. This means that the leftover 15% does not have the Rh factor on their RBCs, so they are Rh-negative. In the situation that Rh-negative individuals receive blood transfusions from Rh positive individuals, a significant issue arises. This is because Rh-negative individuals produce antibodies against the Rh factor (individuals with the Rh positive factor do not produce anti-Rh antibodies). Consequently, individuals with Rh positive blood can receive both transfusions from both Rh positive and Rh negative blood types, whereas Rh negative individuals can only receive Rh negative blood. If a Rh-negative individual received Rh-positive blood, the anti-Rh antibodies from the Rh-negative blood would attack the RBCs from the Rh-positive blood, resulting in the transfusion failure.

With a firm understanding of the significance of blood groups and antigen presentation on red blood cells, let’s now shift our focus to the exchange of fluids within the human body. Every tissue in the body contains fluid because all cells contain intracellular fluid. The presence of fluid is essential for human function as the continuous circulation of fluid between the blood and the body’s tissues facilitates the exchange of dissolved substances such as nutrients and waste. This fluid exchange is regulated by two factors: the hydrostatic pressure of the blood and osmotic pressure.

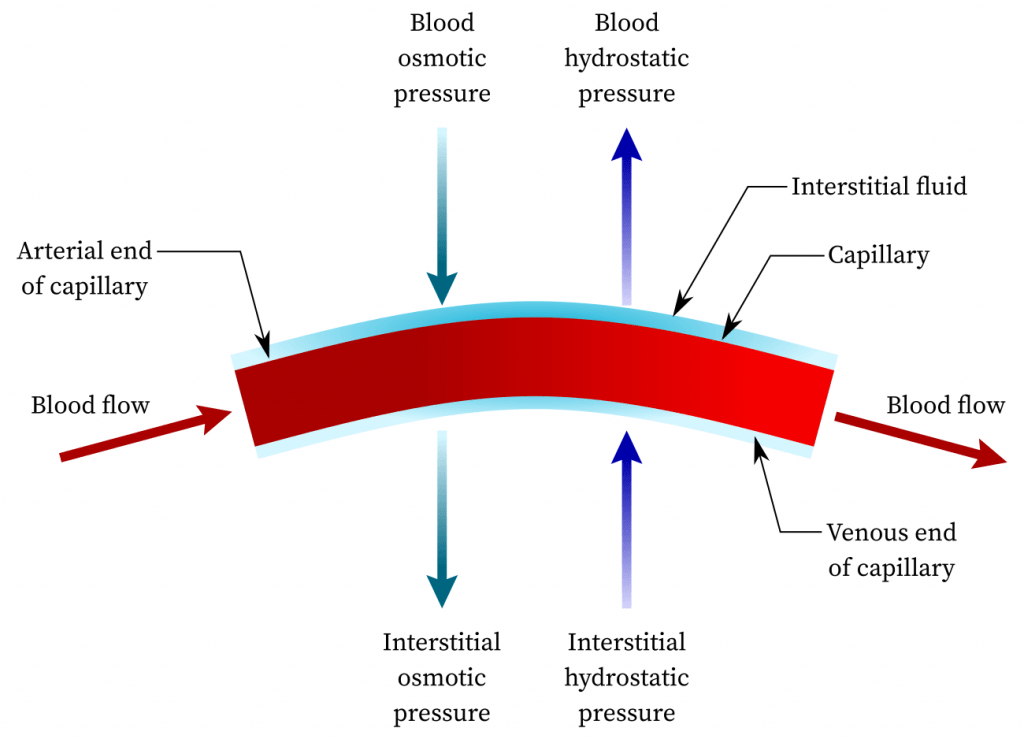

The hydrostatic pressure of the blood is the driving force behind the movement of fluid through the permeable capillary walls into the surrounding tissue. This process depends on factors such as the strength of the heartbeat, blood volume, and blood pressure. Osmotic pressure, on the other hand, acts to draw water from the tissues back into the bloodstream. This force, governed by the principle of equalizing the concentration of dissolved substances on either side of the capillary walls, counterbalances the hydrostatic blood pressure. It’s important to recognize that osmosis is influenced by the presence and concentration of molecules in both the blood and nearby tissue. Substances like salt, sugar, and urea are small enough to traverse capillary walls into adjacent tissue, allowing for the establishment of equilibrium in their concentrations between blood and tissue fluids. However, because proteins are too large to pass through capillary walls, only a small concentration enters the tissue fluid, while the majority remains concentrated in the capillary bloodstream. Consequently, the higher protein concentration in the blood attracts fluid from the tissue back into the bloodstream in an attempt to dilute the elevated protein concentration. This results in the blood having greater osmotic pressure than the tissue fluid.

The dynamic interplay between hydrostatic pressure and osmotic pressure governs fluid exchange within the human body. As blood enters the capillary, it exerts greater hydrostatic force, causing the passage of dilute plasma with low protein content through the capillary walls into the surrounding tissue. As blood continues its journey through the capillary, its hydrostatic pressure decreases due to the loss of this dilute fluid, resulting in a higher concentration of proteins within the blood. Consequently, fluid from the surrounding tissues returns to the bloodstream near the venous transition of the capillaries. The fluid re-entering the capillaries contains essential salts but lacks proteins, as proteins do not permeate capillary walls to return to the bloodstream. Instead, they enter the bloodstream via the lymphatic system.

Lymph channels in the body share a similar structure with capillaries, but they possess greater permeability. This enhanced permeability allows larger molecules, such as proteins, which cannot pass through capillary walls, to traverse the walls of lymph channels and re-enter the circulating bloodstream. Lymph channels and the flowing lymph fluid frequently traverse lymph nodes. Within these nodes, lymphocytes and antibody-containing cells are present, along with phagocytes that engulf foreign and hazardous molecules to combat infection and purify larger molecules, ensuring their safety upon returning to the bloodstream. An interesting example of the protective role of lymph nodes is evident in the black color of lung lymph nodes. This discoloration arises because the air humans currently breathe contains pollutants like coal dust. Thus, lymph nodes aid in purifying the air we breathe, preventing toxic coal particles from entering our bloodstream.

Unlike blood, the movement of lymph through lymph channels is not driven by forceful propulsion. This is because lymph does not have pump-like mechanism similar to a heartbeat. Instead, lymph flow is facilitated by muscle contractions, respiratory movements, and increased fluid volume within the lymphatic system. In cases where lymph flow in one direction is obstructed, lymph can reverse its course and navigate through alternative lymphatic pathways for circulation. Comparable to blood vessels, the smaller lymphatic pathways gradually converge into larger vessels that ultimately drain into two major veins near the right side of the heart.

In conclusion, a highly intricate interplay exists among lymph, tissue fluid, intracellular fluid, and blood. This intricate relationship is essential for facilitating seamless fluid exchange and subsequent purification and utilization of substances such as salts and proteins. In our next anatomy blog post, we will delve into the complexities of the respiratory system, exploring the significance of its structure and function. Stay tuned!