Blood serves as the primary transporter of nutrients to the billions of cells within the human body. Regardless of the individual functions of each cell, such as the contracting ability of cardiomyocytes, all cells depend on the nutrients and materials provided by the circulating bloodstream.

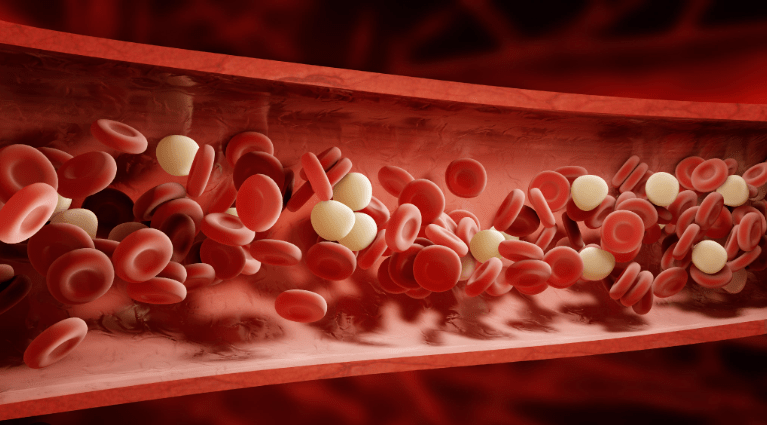

Plasma, comprising over one-half of the blood’s volume, is the fluid component containing many substances essential for blood function. The remaining portion consists of blood cells, which carry vital substances, such as nutrients and oxygen, to the bodies active tissues. Circulating blood is also composed of secretions, which are transported from their gland/organ of origin to the cells that require them, and waste products transported for elimination.

Blood composition is dynamic, with various substances constantly being added and removed, resulting in a net concentration of substances in the blood stream at any given time. Despite variations in children and biological differences between sexes, healthy individuals generally exhibit similar blood constituents, allowing for the establishment of normal levels. These levels fluctuate depending on organ function, with even slight changes indicating potential issues in human health.

Abnormalities in blood composition can signify underlying illnesses. For instance, elevated bile may indicate disease of the liver or bile tract. Elevated urea and urea nitrogen levels, products of cellular metabolism that remain in high concentrations in the blood if not removed by the kidneys, is a sign of kidney dysfunction. Monitoring multiple substance concentrations helps identify abnormal patterns, serving as a warning sign of potential health issues. Therefore, blood is crucial to not only maintaining the wellbeing of the human body, but indicating the quality of human health.

Blood cells fall into two main categories: Red Blood Cells (RBCs) and White Blood Cells (WBCs). Additionally, platelets play a crucial role in blood function. RBCs, also known as erythrocytes, are produced in the bone marrow, specifically in the spine, hip, ribs, and sternum. As RBCs develop in the bone marrow, they lose their nucleus before being released into the blood stream. These worker RBCs live for approximately 4 months after their nucleus disappears, but because these RBCs are continually produced and released in large quantities, the life span of RBCs does not cause a significant problem. RBCs are shaped like a small circular disc with 2 concaved/indented sides. Normally, there are 35 trillion RBCs circulating in the blood stream at any given second. This number is estimated from a tiny drop of blood. At the doctors office, we have all had our blood drawn from a pricked finger into a measured tube. The blood is then diluted in a known quantity of solution, spread evenly on a glass slide, and observed under the microscope. By calculating the number of RBCs on that slide, you can proportionately approximate the number of total RBCs in the body. The exact reasoning and process behind RBC destruction is not fully understood. However, scientists do know that the spleen is integral to RBC destruction. The spleen is a sponge-like organ that lies on the upper left side of the abdomen near the stomach and diaphragm. The blood, instead of easily passing through the channels in the spleen, is slowed in its passage by the intricacies of the spongy structure. This is where RBC break down occurs.

As mentioned above, RBCs (erythrocytes) are red because of their content of hemoglobin, a protein combined with an iron-containing pigment. This compound is crucial since it allows for the transportation of oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body. When you breathe in, highly concentrated oxygen surrounds the blood in the lung. The iron from the hemoglobin rapidly bonds to the oxygen, and the RBCs are released into the blood stream. As the RBCs travel to the organs that utilize oxygen, hemoglobin on the RBC will be surrounded by a low oxygen tension environment. In this environment, the bonds between the iron and oxygen will break, releasing the oxygen to the nearby organ, increasing the organ’s oxygen concentration. The carbon dioxide being released from active tissue cells will be carried by the blood stream back and RBCs to the lungs where it is discharged from the body. While the majority of the carbon dioxide bonds to the hemoglobin to be transported to the lungs, the carbon dioxide also enters the blood plasma and is transported as sodium bicarbonate.

Iron is an essential component of hemoglobin. When there is an iron deficiency in an individual’s blood, fewer RBCs are formed and their pigment (hemoglobin) content is less. This results in anemia, a medical condition characterized by a lack of healthy RBCs containing the correct amounts of hemoglobin in the blood. However, anemia can be easily treated through iron supplements and eating foods with higher iron content. In addition to anemia, there are other reasons as to why many individuals do not have enough RBCs. They could lose RBCs due to hemorrhages; chronic infections could also reduce and weaken the bone marrow, resulting in the destruction of RBCs. Furthermore, there could be a decreased production of RBCs due to a lack of erythrocyte-maturing factor, which is a vitamin that is formed in the stomach and stored in the liver. It is also important to understand that anemia is especially concerning to human health since it accompanies many other illnesses, such as Crohn Disease and Rheumatoid Arteritis. Luckily, RBC restoration is very possible and is spontaneous on illness recovery.

White Blood Cells, also known as Leukocytes, is an overarching umbrella term containing several distinct cell types. One type of WBC is the polymorphonuclear cells, aka “polys,” which are distinguished by the granules that they contain that leave a unique stain in laboratory tests. The most common type of poly cell are neutrophils, which are given their name because they are neutral to acid and basic dyes. When microorganisms, like bacteria or viruses, invade the body, neutrophils are among the first immune cells to react. They migrate to the site of infection and proceed to destroy the microorganisms by engulfing them and releasing enzymes that kill them. Neutrophils act as phagocytes, meaning they ingest and absorb bacteria through a process known as phagocytosis. During this process, the neutrophil engulfs the entire bacterium into its interior, where it undergoes digestion.

Eosinophils are another type of poly cell that have granules that turn bright red when stained with acid dyes. Eosinophils are usually present in small numbers than neutrophils and are involved in host defense against parasites, such as worms, and promoting allergic reactions. Basophils are named because their granules stain with basic dyes. Their role in the immune response is to defend the body from allergens, pathogens and parasites; they also release enzymes to improve blood flow and prevent blood clots. A WBC similar to basophils are mast cells, which are crucial to modulating how the immune system responds to certain bacteria and parasites. Mast cells contain the chemical heparin, which counteracts some of the clotting factors in the blood. All poly WBCs are formed in the bone marrow, just like RBCs. The lifespan and where WBCs die have not been definitively answered, but scientists hypothesize that the majority of them die at the particular site that they function at.

After the poly cells, the lymphocytes are the next most abundant WBC in the blood stream. Lymphocytes are highly present within majority of the organs in the body, especially in the lymph nodes. Lymphocytes are related to the formation of antibodies, which are the mechanism by which the body becomes immune to a specific disease or infection. In the presence of an infection or where dead tissue is being removed, the lymph nodes are especially active and become enlarged. A very common example of this is when you have a sore throat, you might have noticed that tender swollen glands appear. These are actually swollen lymph nodes.

Monocytes are the last group of WCS. Unlike the other WBCs, monocytes have very limited activity in the circulating blood. Monocytes function by finding and destroying germs (viruses, bacteria, fungi and protozoa) and infected cells. Monocytes direct other white blood cells to treat injury and prevent infection. Monocytes are also the source of other immune cells, such as macrophages & dendritic cells. Macrophages are crucial to the innate immune response and are developed in the lymph nodes and spleen. Macrophages are also phagocytes. While poly cells ingest bacteria, macrophages attack and engulf portions of tissue that are destroyed from disease. Macrophages are more active than other cells in phagocytosis and are more specific regarding the removal of foreign particles. In addition to defense against pathogens and removing dead tissue, macrophages are also involved in wound healing and muscle regeneration. Unlike many other WBCs, macrophages do not circulate in the blood stream and are instead localized to specific organs. Dendritic cells are also derived from monocytes and are antigen-presenting cells that help direct the body’s fight against invasive pathogens. These cells also contribute to balancing the body’s tolerance to non-invasive versus self/harmless antigens. Dendritic cells and macrophages have a very unique relationship, as dendritic cell antigens are known to direct macrophage function in the immune response.

To assess physical health, doctors often times count the number of leukocytes in a drop of blood to determine the percentage of each type of leukocyte. Some illnesses can be easily diagnosed from a change in the level of a specific circulating leukocytes. Many illnesses have characteristic increases in leukocyte count, known as leukocytosis. High levels of leukocytes is an indication that your body is currently in defense mode and is fighting off an infection.

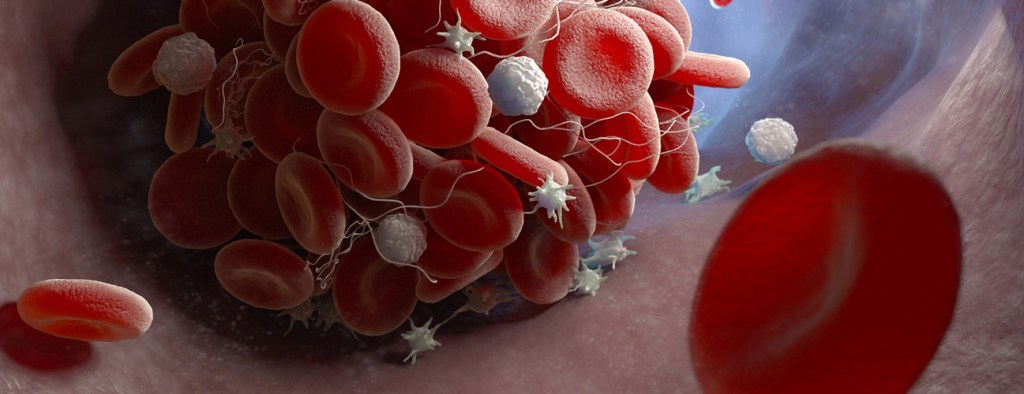

In addition to RBCs and WBCs, another element found in blood are platelets, also known as thrombocytes. Platelets are not actually cells themselves; instead, they are derived from megakaryocytes, fragments of giant cells found in the bone marrow. Platelets have a sticky quality, allowing them to adhere to a rough surface, such as an injured blood vessel. In the presence of blood vessel injuries, platelets clump together, disintegrate, and release thrombokinase, which initiates the process of blood clotting. A variety of different substances are required for blood clotting to occur. These substances will react with each other to form the enzyme thrombin. Thrombin then reacts with fibrinogen, a protein formed by liver cells, converting the fibrinogen into a clot called fibrin.

The equation below represents the relationship between the most important substances in blood clotting:

thrombokinase + prothrombin + calcium + several accessory factors = thrombin

thrombin + fibrinogen = fibrin (the clot)

Thrombokinase is released from platelets or can be found in the blood plasma where it would be activated by platelets. Prothrombin is formed by the liver when enough Vitamin K has been absorbed from the intestinal tract, while calcium is found in the circulating blood in small concentrations. The exact function and mechanism of the accessory factors’ role in blood clotting are still being researched. This begs the question – why doesn’t blood clot all the time if these substances are always present in the blood stream. To start, thrombokinase can only be released when the platelets disintegrate, which occurs as blood flows over a rough surface, like a puncture in a blood vessel (it is no longer smooth). In addition to this, the substance antithrombin is present in the blood and it counteracts the function of thrombin.

The fluid nature of blood depends on the balance of the factors for and against blood coagulation. Clots are commonly formed in the veins of the legs, where pressure is low. This is evidenced by the very common medical condition in middle aged and elderly men & women called Deep Vein Thrombosis. Clots may also originate near an infected area while others can develop in the aftermath of an operation. Blood clots can be easily treated with anticoagulant drugs.

The blood cells of the blood stream are suspended in a fluid called plasma, which is light yellow in color and is of a watery consistency. Blood plasma consists of many important substances:

Organic Constituents:

- Proteins

- Albumin: responsible for maintaining the blood by attracting water into the blood vessels

- Globulins: involved in disease immunity

- Fibrinogen: precursor to fibrin, which is the “meshwork” of the blood clot

- Carbohydrates, such as glucose and simple sugars, for energy production

- Fats, lipids (cholesterol), and phospholipids for storage

- Products of cellular activity & metabolism, like amino acids, urea, & uric acid

- Internal secretions, antibodies, and enzymes that pass from their tissue of origin to the tissue that will utilize them

B. Inorganic Constituents: include sodium chloride, calcium, phosphorus, potassium, and carbonates, which are all present in varying concentrations.

In the next blog post, we will cover the different blood groups, such as A, B, AB, and O, as well as the exchange of fluid that occurs between the active tissue and blood stream.