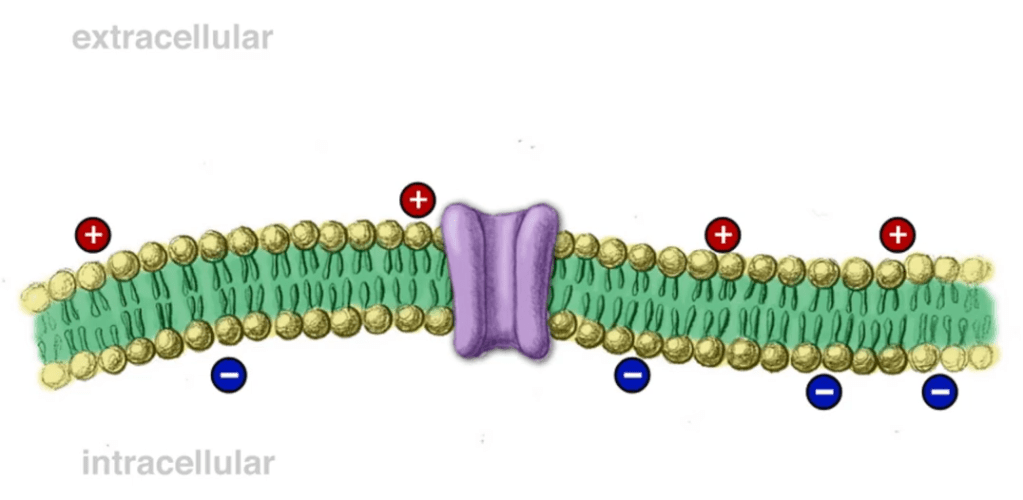

Let us consider a basic schematic membrane, with one side of it being the intracellular side and the other side being the extracellular one. We use a voltmeter, which has a ground electrode that we place outside of the cell and the other end of the electrode that we place inside of the cell, to measure the difference in voltage between the intracellular and extracellular areas. Let’s say that there is an excess of negative ions inside of the cell. This is what leads to a potential difference of approximately 60 millivolts (mV) across the membrane. It is important to remember that when we are determining the membrane potential of a neuron, we are referencing our measurement to the point outside of the cell. Therefore, in this situation, the membrane potential would be -60 millivolts. When at rest, most cells in the human body have a negative membrane potential ranging from -5 to -100 millivolts. In neurons, specifically, the normal resting potential ranges from -40 to -90 millivolts. But, this phenomenon raises a question. How does resting potential and membrane potential occur? The answer lies within how concentration gradients and electrostatic forces drive ion movement across a cellular membrane.

Each side of a neuronal membrane is electroneutral, which basically means that there is no net charge of the solution on each side. This is because in the bulk of the solution surrounding the neuron, for every positive charge, there is a negative charge to balance it out. A positive and a negative charge produce a neutral value (1 + (-1) = 0). The solution itself is charge neutral because of the balancing out of the positive and negative charges that compose it. The membrane potential is derived from the very small imbalance of charges that accumulates very close to the membrane. The imbalance of charges between the intracellular and extracellular side generates an electrical field across the membrane, which results in an electrical potential. This membrane model is very similar to the arrangement of a capacitor.

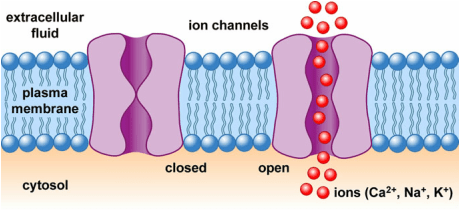

Let us now address how this imbalance occurs. A neuronal membrane is composed of a lipid bilayer, and when there are no openings in the membrane, it means that ions can not pass through it. On both sides of the membrane, there are several positively and negatively charged ions, such as chloride, potassium, sodium, and calcium. For instance, imagine that there are equal concentrations of 75mM of potassium (K+) on both sides. So if there are equal concentrations of ions on each side and the solutions on both sides are electroneutral, how do charge imbalances occur? The answer lies in ion channels, which are passageways in the membrane that allow ions to move from one side of the membrane to the other.

Now, consider that we move positive charges from inside the cell, in the form of potassium ions, out of the cell through an ion channel. Remember, the solution on both sides of the membrane was electroneutral to start because there was a negative ion to match every positive ion. When you remove positive ions from the inside, you will be left with an excess of negative ones. Meanwhile, the previously electroneutral solution on the outside has gained positive charges from the inflow of potassium ions, so it now has an excess of positive charge. At this point, a charge imbalance has developed because the intracellular side is more negative relative to the outside and the extracellular side is more positive relative to the inside. Furthermore, since the convention is to consider the extracellular voltage to be the reference point of 0 mV, the membrane potential inside of the cell would be negative.

The excess charges on both sides of the membrane do not just float around. Instead the laws of physics show that these charges make their way towards the membrane. Using the example previously discussed, the positive charges would line up on the outside of the membrane while the negative charges would line up on the inside of the membrane. So, at this point, ion channels have opened up holes in the membrane, the potassium ions have diffused across the membrane to the outside of the cell, and as a result of this, an electrical potential has developed.

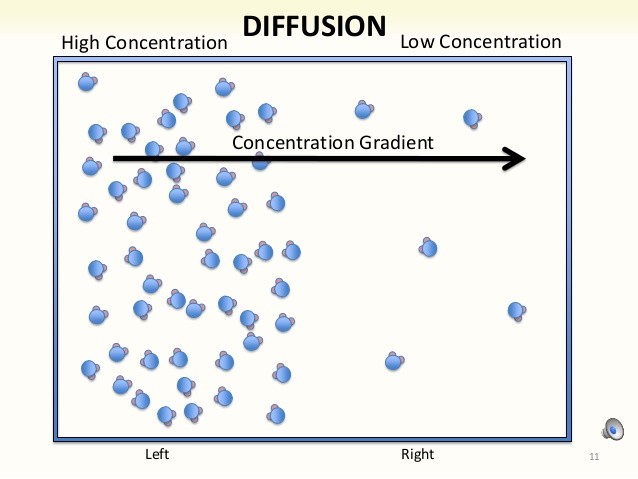

If the diffusion of potassium through the membrane continued to occur till the system reached equilibrium, what would happen to the intracellular and extracellular concentrations of potassium? Most people would normally think that the concentrations on both sides of the membrane would become equal; however, this is not the case. What actually happens is that a small amount of potassium from the inside diffuses through the ion channels to the outside, but the concentration of potassium will still remain greater on the inside. This is because we are dealing with charged particles. If we just had uncharged particles floating through, they would have diffused to the same concentration on both sides of the membrane. The reason why this doesn’t happen for potassium is that it is an ion, a charged particle, so there is an additional force at play – electrostatic force. As we start moving more potassium down the concentration gradient, from inside to outside, that additional net positive charge creates an electrostatic force that repels other positive charges from diffusing out of the cell (inside → outside). But, it is important to remember that not all forces are created equally.

So, how can we create a membrane potential of, for instance, -80 millivolts, which happens to be the equilibrium potential for potassium. Surprisingly, moving just 1 in 100,000 ions across the membrane is sufficient to create a -80 millivolts membrane potential. In cells and neurons, there are trillions of ions inside the cell, so even just moving one in one hundred thousand ions means that we are moving millions of ions outside the cell in order to create equilibrium.

Here is a simple equation to understand this concept:

1/100,000 ions moving x 50,000,000,000,000 ions in a neuron = 500,000,000 ions moving

The key thing to understand is that the electrostatic force, for moving just a tiny fraction of ions to the other side of the membrane, is enough to balance out the diffusion of a large number of particles. This puts into perspective how much stronger electrostatic forces are when compared to diffusion. Furthermore, this means that even though ions move across the membrane to generate a membrane potential, very few ions, in the grand scheme of things, need to actually move, resulting in the concentrations on the inside and outside remaining effectively unchanged. The reason why is that only a tiny proportion of ions move relative to the total number of ions inside and outside the cell. Therefore, when addressing the intracellular and extracellular concentrations, we can ignore the ions that move across the membrane because they do not have a significant impact on the intracellular and extracellular concentrations.

Overall, membrane potentials are established by the diffusion of ions across the membrane through ion channels. The charge imbalance develops due to one side of the membrane being more positive or more negative than the other side. Additionally, despite the diffusion of ions across the membrane, specifically potassium ions as we have covered today, the intracellular and extracellular ion concentrations remain relatively the same. In our next blog, we will go over the significance of Nernst Potential, as well as how to find it.